God's Word

ARCHAEOLOGY

God's Word

ARCHAEOLOGY

The previous lesson is devoted to showing that the text of the Scriptures has been safe-guarded in its preservation, translation, and transmission from its original completion until the present. However, it would be ill-advised and naïve safe-guarded in its preservation, translation, and transmission from its original completion until the present. However, it would be ill-advised and naïve to conclude that the present state of the Biblical text is free of all problems. In fact, the constant challenge of restoring the text to its original form has been the burden of experts in the discipline of Textual Criticism (Cf. Lesson titled “Translation”). The task has been so relentlessly pursued that we may rest confidently in knowing the Biblical text is now closer to the original autographs than ever before.

All of this is well-known. A close look at annotated study Bibles illustrates the extensive effort that has gone into presenting a reliable text. This helps to alleviate concern about the dependability of the Biblical text so far as its transmission and restoration are concerned.

However, there is another area of concern which merits our attention. There are those who concede that the present text very closely follows the original manuscripts and substantially reflects their contents. Their concern is not whether the text has been faithfully transmitted to us; rather, whether the content is true. Were the ancients writing truth; or, were they primarily writing legends, fables, superstitions, primitive folklore, etc., etc.? In other words, do those things we find in a Bible that contains the original content have any factual base? Are they really true? Such questions should be taken seriously, and answers to them should be given carefully. It is very easy to pass error from one generation to another (E.g., there was a time when history books insisted that the earth was flat!).

One of the ways to address this problem is to start with that which can and has been verified. To do this we must confine ourselves to a record of what is reported to have happened and then compare any evidence bearing on that event to see if it supports or confutes the record. Since history is primarily written record of what has happened in the past, we may turn to historical records in the Bible in our investigation of its accuracy. We are aided in this task by utilizing empirical evidence provided by the science of archaeology.

Earlier we stated that two aspects of the subject would be presented in order to make the following point: The Bible has not lost its trustworthiness in its transmission through the centuries. The first aspect, presented in lesson nice, was textual. We examined empirical evidence bearing on the writing, translating, and transmitting of the Scriptures. Out of a veritable sea of resources, we chose manuscripts of major importance to show that the Biblical text, instead of deteriorating, was instead being preserved and restored during the first millennium of its history in the Christian era.

Therefore, as we proceed, we do so with confidence that we are using Bible texts that retain what was originally written. Notwithstanding the problems inherent in the continuing challenge of perfecting the Biblical texts to the greatest extent new evidence will allow, the reader of the Bible today may rest assured that the original language texts upon which the Bible (translation) is based have been substantiated to a remarkable degree.

But does it necessarily follow that the trustworthiness of the text includes both its state and content? In other words, does the Biblical text say now what it originally said; and, is what was originally said true? This brings us to the second aspect of the “Verification of the Bible” – Archaeology. The methodology will be similar to that used in our look at texts. We will continue using textual materials to demonstrate that the present base texts have been conscientiously transmitted to us. We will also be using archaeological evidence to show that the Bible does indeed accurately record historical events, many times in amazing detail.

Just as we chose major manuscripts from many to use as chief witnesses to accomplish our task in the previous lesson, we now choose outstanding archaeological discoveries from many to see what bearing they have on illustrating the historical accuracy of the Bible. The reader will be aware, of course, that the work of field archaeologist themselves and by other scholars from related disciplines such as anthropology and paleography. This evaluation process is often quite lengthy and sometimes leads to reassessment of the meaning and significance of archaeological discoveries.

In spite of the frustration this occasionally produces, it often results in a more accurate understanding and deeper insight into the available evidence. Therefore, we have deliberately chosen archaeological discoveries that have stood up under scrutiny. They serve our purpose well as we examine how archaeology has made many contributions in verifying the Bible, including the following ways:

(1) It provides a general background to the history of the Bible.

(2) It supplements the Bible accounts.

(3) It helps in understanding and translating difficult Bible passages.

(For more information on these themes, see Merrill F. Unger, Archaeology and the New Testament; and J. A. Thompson, The Bible and Archaeology.)

It is axiomatic that what is recorded in the Bible did not happen in a vacuum. The Bible unfolded within the context of history. This means there should be some historical relationship between what happened in the Bible and what was going on in the world related to and contemporary with the Bible. In other words, there should be some background for the stage upon which the events of the Bible occur. Indeed, there is. When this background comes to light, often it adds credibility to the Biblical record. Some “background” examples follow.

The Bible says very little about Ur. This city is specifically mentioned four times in the Old Testament, always with the descriptive phrase, “Ur of the Chaldeans” (Genesis 11:29, 11; 15:7; Nehemiah 9:7). These references speak of God’s instructions to Abram (Abraham) to leave Ur and go where he would be directed (Canaan). The full saga of Abraham is well known. But what about Ur? Was Un an historical place? If so, what was it like? What did Abraham leave when he left Ur? Where was Ur located? These questions cannot be answered from the biblical text. However, archaeology supplies the answers. We now have rich background information about Abraham’s native city.

The ancient site of Ur was excavated by Sir Leonard Woolley from 1922-1934 under the auspices of the British Museum and the University of Pennsylvania. The site is located in old Southern Babylonia about 150 miles southeast of Babylon and about ten miles west of the Euphrates River. From this ancient site it is about 100 miles south to the present Persian Gulf shoreline.

Excavations indicate Ur was an important Sumerian city. Civilization was far advanced as illustrated by discoveries of highly developed writing, historical and religious records, high math, an organized school system, elaborate art, and a sophisticated culture. A great tower about seventy feet high, surrounded by living quarters for the priesthood and storage rooms to house the offerings, was located in the center of the city. “The Babylonian word zigguratu meant ‘temple tower.’ In Babylonian cities it was the center piece for the worship of various Mesopotamian gods. The ziggurate at Ur was about 200’ long, 150’ wide, and 70’ high” (E. M. Blaiklock).

Much pomp and ceremony must have been involved in the worship of the moon god Nanna. Belief in an afterlife was made evident by the provisions found stored in the royal tombs.

We can appreciate better the fact that Abraham made two great pilgrimages. One was geographical – from Sumer to Canaan; the other was spiritual – from the idolatrous city of Ur to friendship with the one true and living God (2 Chronicles 20:7; Isaiah 41:8; James 2:23).

Ur means “light.” This seems appropriate since the city inhabited for about 3,500 years. During its periods of highest achievements, Ur developed one of the most advanced civilizations of the ancient world.

The next example has to do with the Hebrews and their experiences while in Egypt. Interestingly enough, there is only one verse in the Bible devoted to the period between the death of Joseph and the time of Hebrew captivity. “But the sons of Israel were fruitful and increased greatly, and multiplied, and became exceedingly mighty; so that the land was filled with them'” (Exodus 1:7).

So far as archaeology in Egypt is concerned, the only time the name “Israel” appears in inscription is on a large black granite stele erected by Merneptah, the son of Ramses II, in about 1230-1220 B.C. in his mortuary temple at Thebes. The stele speaks of Merneptah’s military successes in Palestine and gives a list of his conquests, including the statement, “Israel is laid waste, his seed is not.” The stele was discovered by Flinders Petrie and published by him in 1897. It is now located in Cairo, Egypt. (The entire text may be found in Ancient Near Eastern Texts Relating to the Old Testament, James B. Pritchard, ed.) Although this is evidence that the Israelites were in the Promised Land at that time, it does not address the Egyptian captivity question. Therefore, to what may we turn for background information that will provide credibility for the Biblical account of the long Israelite stay in Egypt? Two different areas provide ample testimony.

First, we note that place names are significant indicators of relationships between geographical areas and the people who settle and live in those areas. Dr. James E. “Gene” Priest provided a wonderful example: “When my wife and I lived on the East Coast, we seized every opportunity to travel along the Eastern Seaboard from Virginia to Maine. We were enthralled by the beauty and history of that part of our nation. However, perhaps the most revealing and intriguing discovery we made was the significance of place names we encountered along the way. They revealed background. As Americans who speak English as our first language, we were particularly captivated by the implications of English place names. A few of them are Williamsburg and Jamestown in Virginia, Baltimore in Maryland, New York City in New York, New London in Connecticut, Plymouth in Massachusetts, and Manchester in New Hampshire.”

Considering the implications of the above, Dr. Priest continued: “Williamsburg and Jamestown conjured up thoughts of English royalty. Baltimore recalled the Barons Baltimore of English prominence. Maryland echoed English royalty. New York was a name with an ancestral psyche deeply imbedded in Britain (House of York, Dukes of York, City of York, Yorkshire County). New London was self-explanatory. Plymouth was a strategic city in Devonshire, England for well over one half millennium. Manchester was grounded in the illustrious Dukes of Manchester and the importance of the city of Manchester through the centuries.”

All of these names are so interlaced with our history that they give us a profile of our past. The same is true with place names we find in the Bible that reflect an Egyptian interface with the Israelites. Just as the English place names we have mentioned will not allow us to deny our connection with Britain, the place names we now note will not allow us to deny the historic connections the Israelites had with the Egyptians.

We are told in the Bible that the Israelites settled in the land of Goshen (Genesis 46:26ff.). Although the name is not found outside the Bible; in the Biblical account it is identified with the Eastern Delta of the Nile. It is called “the best of the land” (Genesis 45:10, 18; 47:11, 27). Semitic place names found in this Delta region dating from the New Kingdom period in Egypt (ca. 1552-1070 B.C.) indicate a long Semitic occupation before that time (William Foxwell Albright). Some of these mentioned in the Bible are Succoth (“booths,” Exodus 12:37), Migdol (“fortified city,” Exodus 14:2).

As mentioned above, place names of longstanding give a profile of the past. Just as Our English past is reflected in place names along the Eastern Seaboard of the United States, so the Semitic place names in the general northeastern Delta region of the Nile River establish a presence of Semites in Egypt’s past. Since the New Kingdom era in Egypt includes the latter period of Hebrew slavery, it is safe to conclude that the foreign influence there, illustrated by these place names, was not merely Semitic in general, but strongly Israelite.

But why would the Egyptians, who feared and hated their foreign slaves, have retained such names after the slaves were gone? After hundreds of years, the historic significance of names is often lost as they are assimilated into a changing culture. Who in the U.S.A. thinks of Yorkshire, England when New York is mentioned? Who thinks of the English Dukes of Manchester when Manchester, New Hampshire, is referred to? The significance of names may be lost, but the presence of the names in the literature is evidence from the past. Yes, the Israelites were in Egypt. The biblical story of their presence there is not fiction. It is history with rich background from outside the Bible that lends authenticity to the Bible record.

A discussion of personal names may be added to what has been said about place names. Although personal names are treated more casually in modern times than in antiquity, it is still true that one can often distinguish the ethnic orientation or nationality of a person by the name he or she has. For example: Smith has English roots, Garibaldi is Italian. Clemenceau is French. Rommel is German, etc. This is obvious. It is also interesting to find that “foreign” names do not, as a rule, intrude in family genealogies. It would be surprising to find a child named Abu listed in an English family tree. It would also be unusual to discover that French parents had named their infant daughter Indira. Abu and Indira are fine names; the former being Arabic and the latter Indian. However; if such names were found in English or French family genealogies it would likely reflect an unusual set of historical events leading up to the name selections. This brings us to the point.

In the Bible we find there were Levites who gave their children Egyptian personal names. A few examples will suffice. In Exodus 6:24 we find that Assir was one of the sons of Korah. Assir means “prisoner.” 1 and 2 Chronicles are the last two books of the Hebrew Bible. In 1 Chronicles we find among the priesthood one whose name is Pashhur (1 Chronicles 9:10-13). In contrast to Assir, Pashhur means “free.” After the Egyptian captivity, we find that Eli had two sons, Hophni and Phinehas, who were priests serving at the tabernacle while it was at Shiloh, (1 Samuel 1:3). Their names mean “strong” and “oracle,” respectively. In Genesis 46:11 we find one of the sons of Levi was named Merari; that is, “bitter.” All of these names whose meanings are given are Egyptian. It would be difficult to explain why Israelite parents would give their children Egyptian names if they had never been associated with Egypt or Egyptians. The overpowering logical conclusion is that the Israelites were in Egypt.

The name Moses falls into a special category because of the unusual circumstances of his birth and subsequent rescue from the Nile River by the daughter of Pharaoh (Exodus 2:1-10). She realized the infant was a Hebrew. Not knowing his name, she apparently merely described him by use of the Egyptian MS = “child.” This Egyptian noun appears often in the names of Pharaohs who were thought to be offspring of the gods. E.g., Thutmoses III (child of Thoth) was among those kings who ruled Egypt during Israel’s captivity.

The infant was placed in the care of his mother, Jochebed, who returned him to Pharaoh’s daughter after he was weaned. “… and he became her son; and she named him Moses (Heb. Mosheh), for she said, ‘Because I drew him out of the water’” (Exodus 2:10b). The Hebrew word for “draw out” is “mashah.” There is no etymological connection between the Egyptian word M(o)s(e) = “child” and the Hebrew word m(a)sh(a)h = “draw out.” However, there is a play on words, a pun that provides the child his Hebrew name – Moses. This episode cannot be satisfactorily explained without the presence of the Israelites in Egypt.

The next archaeological discovery we note that provides insight into Bible backgrounds comes from the New Testament. In fact, it has to do with the language of the New Testament. We have already mentioned this topic (Cf. Lessons Five and Eight). Now we point out that the language of the New Testament has always presented special challenges. It did not readily fit into a specific category. Several factors contributed to this. Those who worked with the text itself usually did so with certain assumptions. Some scholars thought it was an altogether different form of Greek from its Classical ancestor. Others saw the N.T. text as non-classical Greek that had been vulgarized by incompetent scribes, and there were those who looked upon the N.T. text as a special vehicle written in “Holy Ghost” language.

Reasons for these differing assumptions are easy to find. Although in Greek, the Greek of the N.T. cannot be equated with the Classical Greek of earlier centuries. They are not literary equivalents. Yet, the N.T. is in Greek; and, in certain books, such as Hebrews and Luke, one often finds evidence of “classical elegance.” It is also the case that the Jewish writers of the N.T. were not writing in their primary language (Hebrew/Aramaic). Therefore, their Greek contains many Aramaisms which are not to be perceived as incompetent corruptions. Finally, the “Holy Ghost” view was likely assumed by default, since no other explanation seemed satisfactory.

This scenario changed dramatically at about the turn of the 20th Century. Flinders Petrie excavated at the Egyptian Fayyum (Henry O. Thompson). He found many papyrus manuscripts stored in sarcophagi (coffins). From I897 to 1900 A.D., B. P. Grenfell and A. S. Hunt worked further south at Oxyrhynchus over 100 miles south of Cairo and a few miles west of the Nile River. When they dug up a sacred crocodile cemetery they found the animals had been filled with papyrus manuscript scrolls before burial.

These finds, along with others, brought linguistic scholars to a better understanding of the language of the New Testament. Most of their writings were penned sometime during thy first millennium A.D. and covered a wide variety of subjects. Many contain Biblical texts; Gustav Adolf Deissmann took a leading role in establishing that the language of the New Testament was not the result of ignorant men trying to mimic Classical Greek. Neither was it a unique “holy” language. Rather, the New Testament Greek was the same type of Greek found in the Oxyrhynchus documents dating through the era of writing and canonization of the New Testament. This tremendous discovery solved the riddle of New Testament Greek. It was not extraordinary at all. In fact, it was Koine (“common”) Greek.

How fitting that the message for the ages is couched in the language of ordinary people! This background material has done much to enrich our knowledge of, and appreciation for, the New Testament. In addition, the Koine Greek of the papyri often yields greater insights into specific New Testament words. For examples: In 2 Corinthians 1:22 (KJV) we are assured that “(God) hath sealed us, and given the earnest (arrabon) of the Spirit in our hearts.” After the Oxyrynchus papyri were unearthed, we now find the translation of arrabon rendered in the NASB as follows: “(God) also sealed us and gave us the Spirit in our hearts as a pledge.” In the NIV the translators chose the papyri meaning of the term as “down-payment,” and the reading became “He anointed us, set his seal of ownership on us, and put his Spirit in our hearts as a deposit, guaranteeing what is to come.”

Again, in Hebrews 11:1 (KJV) “Now faith is the substance (hypostasis) of things hoped for, the conviction of things not seen.” Influenced by the Koine texts of Oxyrhynchus, the NASP translation became “Now faith is the assurance of things hoped for, the conviction of things not seen.” Finally, the NIV translation, based upon further insights from the Oxyrhynchus Koine Greek papyri meaning of hypostasis as “title-deed,” became “Now faith is being sure of what we hope for and certain of what we do not see.”

We have been examining how biblical archaeology often provides a general background for the history found in the Bible. We saw how excavations at the ancient city of Ur opened our eyes as never before to the world of Abram (Abraham) and the background from which he came. We found the Hebrew place names in Egypt and Egyptian personal names worn by the Israelites gave credence to the historical presence of the Israelites in Egypt as the Bible describes. We saw how the discovery and study of the Koine Greek papyri of Oxyrhynchus, Egypt, helped solve the mystery of the perplexing Greek of the New Testament, and, in many instances, gave us an enriched text. Yes, archaeology does provide backgrounds to the Bible which testifies to its historical accuracy.

Biblical archaeology also supplements Bible history in a remarkable way. Background information such as Abraham’s Ur and the Israelites' Egyptian personal names provides an historical context for the biblical account. Supplemental information giving additional facts not found in the Bible adds assurance to the historical account that is found in the Scripture. The following examples illustrate the important role Biblical archaeology has in this regard. The Empire of Assyria (Assur) is mentioned in the Bible well over one hundred times, beginning in Genesis 2:14 and continuing until Zechariah 10:10-11. Assur is also translated about two dozen times as “Assyrian” when referring to citizens of Assyria. Obviously, the history of Assyria and the Assyrians has a prominent place in the Bible. Indeed, Assyrian kings are mentioned in the Bible, along with some their exploits. For examples: Tiglath Pileser III (745-727 B.C.), called “Pul” in the Bible (1 Chronicles 5:26), was paid tribute money by Menahem, king of Israel, to keep from being destroyed (2 Kings 15:19, 20) (James B. Prichard). Shalmaneser V (726-722 B.C.) became king in Assyria after the death of Pul, his father. It was during the reign of Shalmaneser V that Ahaz, king of Judah, appealed to him for protection against Syria (2 Kings 16:6ff.).

Like the above, several other Assyrian kings are named in the Bible more than once (E.g., Sennacherib [2 Kings 18:13; Isaiah 37:37], and Esarhaddon [2 Kings 19:37; Ezra 4:2]. However, one is mentioned by name only once in Scripture. He is the focal point of our survey. Isaiah wrote, “In the year that the commander came to Ashdod, when Sargon the king of Assyria sent him and he fought against Ashdod and captured it…” (Isaiah 20:1). King Sargon was a puzzle to Bible historians until about 150 years ago. Some scholars had questioned the accuracy of Isaiah’s statement on the grounds that an Assyrian king powerful enough to send armies to capture foreign cities would not merely be mentioned in passing. The name “Sargon” was doubted in the Bible and absent from all available extra-biblical literature. That is, until 1842. That year Paul Emile Botta, a French diplomat assigned to Mosul, dug at Khorsabad, about twelve miles northwest of ancient Nineveh. This site proved to be the great capital city of Sargon II where his ornate palace was found. Aiding Botta in the work of copying inscriptions and making drawings during 1844 was the French scholar E. Flandin. In the 20th century the work was resumed by Edward Chiera and the Oriental Institute of Chicago from 1929 to 1935.

An amazing picture unfolded. In addition to an array of buildings, there were sculptures, inscriptions, bas-reliefs, clay tablets, city walls with scenes of Assyrian life depicted, lists of kings and other historical information such as military campaigns, etc. The evidence portrayed the historical presence of one of the most powerful and prominent kings in the long saga of Assyrian royalty. It turned out that Sargon II and his predecessor, Shalmaneser V, were kings in Assyria during the fateful closing days and tragic end of the Northern Kingdom of Israel. “Now it came about in the fourth year of King Hezekiah, which was the seventh year of Hoshea son of Elah king of Israel, that Shalmaneser king of Assyria came up against Samaria and besieged it. And at the end of three years they captured it; in the sixth year of Hezekiah, which was the ninth year of Hoshea king of Israel, Samaria was captured. Then the king of Assyria carried Israel away into exile to Assyria, and put them in Halah and on the Habor, the river of Gozan, and in the cities of the Medes, because they did not obey the voice of the Lord their God …” (2 Kings 18:9-12b).

Although Shalmaneser V was king of Assyria when Samaria fell, it is thought that he died shortly thereafter and Sargon II completed the deportation of the Israelites (Cf. Jack P. Lewis, Archaeological Backgrounds to Bible People). At any rate, Sargon took generous credit for this final blow to the Northern Kingdom. Lewis provides one of Sargon's inscriptions: “I besieged and conquered Samaria (Sa-me-ri-na), led away as booty 27,290 inhabitants of it. I formed from among them a contingent of 50 chariots and made remaining (inhabitants) assume their (social) positions. I installed over them an officer of mine and imposed upon them the tribute of the former king.”

Archaeology has made valuable contributions to biblical studies; but seldom has archaeology more convincingly and completely supplemented historical accounts found in the Scriptures as in the case of many Assyrian kings. This included Sargon II, mighty king of Assyria from 722-705 B.C.

As history shows, even kingdoms of powerful stature rise and fill. Assyria was one such kingdom. The Babylonian and Mede coalition successfully overthrew the Assyrians in a battle at Nineveh in 612 B.C. Although the Assyrians regrouped and fought again at Haran in 609 B.C., they were again defeated (John Bright), though the Egyptians under Pharaoh Neco came to their aid (2 Chronicles 35:20-24). Finally, in 605 B.C., the remaining Egyptian forces entrenched at Carchemish were forced to flee (Cf. Jeremiah 46:1-12) by the Babylonians under Nebuchadnezzar and given a severe blow at Hamath.

Then the Babylonians marched into Palestine and took Judah. The reigning king, Jehoiakim, was allowed to remain on the throne as a puppet king. After his death, Jehoiachin, his son, came to the throne for about three months. But in 598 B.C. King Nebuchadnezzar removed him and deported him to Babylon, the capitol of the new Babylonian kingdom, along with the royal family and great numbers of the Judeans. Amazing extra-biblical corroboration of this event is reflected in the “Babylonian Chronicle” found in ancient Babylon (A collection of inscribed clay tablets giving concise accounts of major internal events in Babylonia during the time of Assyrian rule).

It reads as follows: “In the seventh year, the month of Kislev, the king of Akkad mustered his troops, marched to the Hattiland and encamped against the city of Judah and on the second day of the month of Adar he seized the city and captured the king. He appointed there a king of his choice, received its heavy tribute and sent them to Babylon” (Cf. J. A. Thompson, The Bible and Archaeology, where he relates this Babylonian Chronicle account to Biblical history in 2 Kings 24:12-16).

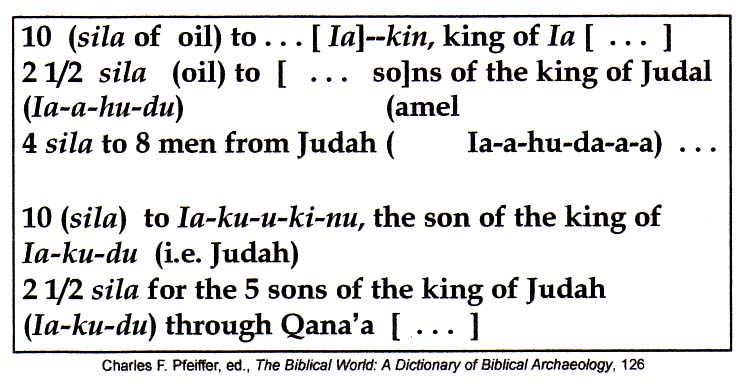

Extensive archaeological work has been done at the ancient capital of Babylon for oven 200 years by many individuals and teams (Charles F. Pfeiffer). It is scarcely possible to imagine the extent and importance of the discoveries. The following inscription, also dating from the reign of Nebuchadnezzar, is mentioned as a companion to the above quotation to illustrate the detailed way archaeological finds often verify the history of the Bible. The one just noted shows that Jehoiachin, along with the royal family and many others, was deported to Babylon by Nebuchadnezzar. The following is even more surprising. These tablets were excavated at Babylon by Robert Koldeway and his German team during their work from 1899 to 1914. They date about 592 B.C. They are documents (ration lists?) showing deliveries of oil to war prisoners and others who were dependent upon royal largess. The king of Judah and his five sons are among those recipients.

What an astounding supplemental confirmation from archaeology of both the deportation of an Israelite king and his family and the provision for that king and his sons while they are in captivity!

When one turns to the New Testament, one finds there is no lack of archaeological supplementary evidence bearing on many historical events and places recorded there. One example with regard to a place will suffice to illustrate how extensive this evidence can be.

Caesarea by the Mediterranean Sea is mentioned fifteen times in the NASB and seventeen times in the NIV. All of these references are found in the Book of Acts. They are related to the missionary activities of Peter and Paul and other disciples. Briefly, we are told:

1. Philip the evangelist “preached his way” from Azotus to Caesarea after he had baptized the Ethiopian eunuch (8:40).

2. Paul was sent away by his brethren from Jerusalem to Tarsus via Caesarea to escape death threats (9:30).

3. Cornelius, a centurion of the Italian battalion, was stationed in Caesarea (10:1).

4. By God’s providence, Peter was sent to Cornelius in Caesarea to preach the Gospel to him (10:24).

5. Peter reported the success of his Caesarea mission to the Jerusalem church (11:11).

6. King Herod left Jerusalem for Caesarea after Peter escaped from prison and James was martyred (12:19).

7. Paul visited the church in Caesarea coming off his second missionary tour (18:22).

8. As Paul was returning from his third missionary journey, he stayed several days in Caesarea with the evangelist Philip and his family (21:8).

9. When Paul left Caesarea for Jerusalem, disciples from Caesarea traveled with him (21:16).

10. When Paul’s life was endangered in Jerusalem, the Roman military secreted him in Caesarea (23:23).

11. Paul was presented to the Roman governor Felix when the governor arrived in Caesarea (23:33).

12. Ananias the high priest, and a group from Jerusalem, came to Caesarea and brought changes against Paul (24:1, NIV).

13. Festus, a new Roman governor, arrived in Caesarea and visited Jerusalem (25:1).

14. Festus announced he would return to Caesarea and hear Paul’s case (25:4).

15. Paul appeared before Festus in Caesarea and appealed to Caesar (25:6).

16. King Agrippa and Bernice arrived in Caesarea to pay their respects to Festus (25:13).

17. Festus spoke to Agrippa about the Jews in Jerusalem and Caesarea who wanted Paul killed (25:24, NIV).

Although frequently mentioned in Acts, we know scarcely nothing about Caesarea from the Bible. We deduct that it was a seaport on the eastern shore of the Mediterranean Sea located not far from Ptolemais. It seemed to be about a two day journey from Jerusalem, and served as a hub of entry and departure for voyagers coming and going in the Roman Empire. What supplemental information does extra-biblical history and archaeology give us concerning Caesarea?

Flavius Josephus, a Jewish historian of the first century (ca. 37 A.D.-100 A.D.), wrote in detail about this ancient site which eventually was called Caesarea Sebastos (Augustus), Caesarea Palaestina, or Caesarea Maritima (Josephus). Its location on the Palestinian coast is about 23 miles south of Mount Carmel and 65 miles northwest of Jerusalem. The Phoenicians had a fortification there as early as the third century B.C. which was called Strato’s Tower. Near 100 B.C. it was under the Jewish dominion of the Hasmonean ruler Alexander Jannai.

After the Romans took Judea in 63 B.C., Strato’s Tower was placed under Roman rule from Syria. Gaius Julius Caesar Ochavianus became the first emperor of Rome when, in 27 B.C., the Roman Senate conferred upon him the title Augustus (magnificent, dignified, grand; etc.). Under the rule of Augustus, Herod the Great became king of Judea and the coastal region, including Strato’s Tower. Among Herod’s many building projects on the site was a port and city which he named “Augustus’ port” and “Caesarea,” respectively. The project was begun in 23 or 22 B.C. and completed in ten or twelve years, after which it was lavishly dedicated to Caesar Augustus (Cf. Moshe Pearlman and Yaacov Yannai, Historical Sites in Israel, for excellent pictures, detailed descriptions, and discussion of the work of individual archaeological teams, plus helpful bibliography).

How does archaeology contribute to a better understanding of biblical Caesarea and its port? The site covered about 8,000 acres, the largest in all of Palestine. The city had streets well laid out, and there was an elaborate sewer system. Caesarea was the royal residence of the Roman authorities from 6 A.D. to 66 A.D. So, in addition to residential and business areas, there were the royal quarters and palace. An ornate temple was built in honor of Augustus. Other buildings, some of which postdate the first century, included a hippodrome built in the third century A.D., a theater south of the harbor, and an amphitheater in the north section of the city (Cf. Keith N. Schoville, Biblical Archaeology in Focus, for New Testament related finds including an inscription on a stone in the Roman theater which read Tiberieum/[Pon]tius Pilatus/[Praef]ectus Iuda[eae] – “Tiberius [the Roman emperor of the period]/Pontius Pilate/Perfect of Judea.” This is the first archaeological evidence of Pilate, under whom Jesus was crucified). Water was brought some ten to thirteen miles to the city from Samaria by an imposing aqueduct system utilizing gravity flow.

These building marvels made Caesarea a very impressive city reflecting Roman influences, style, and architecture. In addition, “Augustus’ port” was perhaps the crowning achievement of Herod at Caesarea (Robert J. Bull). It had a north and south harbor sheltered by two enormous breakwaters extending 1,500 feet out into the water. The north breaker was about 150 feet wide. Blocks weighing more than 50 tons were found in these breakwaters. The breaker on the south, measuring some 200 feet wide, sat in 120 feet of water. This arrangement provided a protected area of about 40 acres of water. Some of the limestone block used for these protective breakwaters measured up to 49 by 39 by 5 feet. Most ingenious was the use of the concrete blocks that anchored the breakwaters. Their formation utilized the largest technology to produce hydraulic concrete which could be poured and allowed to set under water (Robert L. Hohlfelder).

Enough has been said to demonstrate the supplementary role of secular history and archaeology to historical accounts found in the Bible. Caesarea Maritima, although an extensive and detailed example of King Herod’s building projects, is merely one of numerous such finds. Another important site, built on by both Herod the Great and his son Philip, is being excavated by a consortium of American universities such as Pepperdine. It is Caesarea Philippi – not to be confused with Caesarea Maritima. It was at Caesarea Philippi that Simon Peter made the great confession to Jesus, “Thou art the Christ, the Son of the Living God” (Matthew 16:16, KJV). Evidence from these sites, and others, repeatedly supplements Biblical historical records and points to a strong verification of biblical text.

Archaeology also contributes to better understanding and translation of many Biblical passages. Two examples from the Old Testament and one from the New Testament show how archaeological evidence may add to our appreciation for, and confidence in, the verified text of the Bible.

Earlier we noted that Pharaoh Neco came to the aid of the desperate Assyrians who were being battered at Carchemish on the Euphrates by the coalition of Medes and Babylonians. When King Josiah of Judah intercepted Neco and his Egyptian troops on the Plain of Megiddo, he was killed in the battle. The text of 2 Chronicles 35:20ff. does not tell us whether the Egyptians were going to fight for or against the Assyrians. Neither are we told whether King Josiah knew the intentions of Pharaoh Neco. However, there is a parallel passage describing this event in 2 kings 22:28-30a. In this passage (v. 27), it is said that “Pharaoh Neco king of Egypt went up to the king of Assyria to the River Euphrates”.

Through the centuries English translators have thought that Neco was going up to fight against the Assyrians. With this in mind, they translated the Hebrew preposition ‘al (above, beside, against, upon, to) as “to,” in the sense of “against.” However, the wealth of evidence now available from ancient Babylon indicates that Pharaoh Neco was going up to fight for the Assyrians, not against them (Gaalyah Cornfeld). Consequently, English readers now find in the NIV the following translation: “While Josiah was king, Pharaoh Neco king of Egypt went up to the Euphrates River to help the king of Assyria. King Josiah marched out to meet him in battle, but Neco faced him and killed him at Megiddo” (2 Kings 23:29).

Thus, with archaeological aid, we have a clearer rendition of a passage and an enlightened perspective on an historical event.

Again, one finds an improved translation in Joshua 11:13, “However, Israel did not burn any cities that stood on their mounds, except Hazor alone, which Joshua burned” (NASB). “Yet Israel did not burn any of the cities built on their mounds – except Hazor, which Joshua burned” (NIV). The KJV rendering of this verse is, “But as for the cities that stood still in their strength, Israel burned none of them, save Hazor only; that did Joshua burn.” This is the only place in the KJV where the word tel is translated “strength.” Biblical archaeology has long since reminded us that tel ordinarily means “mound” – a word that describes a “heap” or a “ruin” marking the site of earlier occupation (compare KJV Deuteronomy 13:16; Joshua 8:28; Jeremiah 30:18 to NIV).

Recent translations such as the NASB and NIV call to our attention that Joshua 11:13 is speaking of the location or situation of the cities instead of their relative strength. After all, Hazor was the strongest and most impregnable of the cities of those northern kingdoms (Joshua 11:10, 11); yet, Joshua burned it. However, he did not destroy the weaker cities that stood on their mounds – but not in their strength. Thus, we now have a better understanding than did earlier generations of readers regarding what God’s Word actually says in this passage.

Earlier we discussed the Oxyrhynchus papyri finds to illustrate the role they played in establishing that the New Testament was written Koine (“ordinary”) Greek. This marvelous cache of texts also illustrated how textual discoveries often illuminate individual words or phrases in the New Testament. This was a very important contribution.

Imagine you are a translator working with a committee of New Testament scholars about 100 years ago. You have many texts from which to work, including the venerable Alexandrian, Sinaiticus, and Vaticanus trio. Yet, there is a frustrating problem. You realize that often there are words found in the New Testament and nowhere else. Sometimes a word is an hapax legomenon, i.e., a word that appears only one time in the entire New Testament. How will you translate such words? No help is forthcoming from word lists, concordances, or dictionaries. In other words, there is no instant realization of what such isolated words may mean. This is where the translator must rely heavily on the context of a word to deduct its meaning. The papyri documents were often of significant help in focusing a more precise meaning on many New Testament words. The Koine Greek papyri texts contained many words which were known to exist only from the New Testament until the papyri discoveries.

These troublesome words of the New Testament were often found in the papyri in contexts which made their meaning obvious. This obvious meaning was then taken to where the word appeared in the New Testament. Careful analysis in this procedure often provided fresh insight into the meaning of the word as used in the New Testament. The following brief list of words found only in the New Testament until the papyri were discovered illustrates how the findings of archaeologists often help in translating and understanding the text of the Bible, especially the New Testament in this case. In the examples, the KJV renderings represent the pre-Oxyrhynchus discoveries. The NASB and NIV translations show the more precise meanings made possible by the papyri finds. “And they came to Jesus, and see him that was possessed with the devil, and had the legion, sitting, and clothed (himatizo/himatismenon) and in his right mind: and they were afraid” (Mark 5:15, KJV). [NASB and NIV render “clothed” as “dressed.”].

“After a long time the lord of those servants cometh, and reckoneth (synairo/synairei) with them” (Matthew 25:19, KJV). [NSAB and NIV render “reckoneth” as “settled accounts.”].

“There was not found that returned to give glory to God, save this stranger” (allogenes) (Luke 17:18, KJV). [NASB and NIV render “stranger” as “foreigner.”].

“But I keep under my body, and bring it into subjection: lest that by any means, when I have preached to others, I myself should be a castaway” (adokimos) (1 Corinthians 9:27, KJV). [NASB and NIV render “castaway” as “disqualified.”].

“O foolish Galatians, who hath bewitched you, that ye should not obey the truth, before whose eyes Jesus Christ hath been evidently set forth (prographo/proegraphe) crucified among you?” (Galatians 3:3, KJV). [NASB renders “evidently set forth” as “publicly portrayed.” NIV renders “evidently set forth” as “clearly portrayed.”].

Seeking verification, we have drawn from the abundant storehouses of textual and archaeological evidences having a bearing on the Bible. We found the ancient manuscripts support the conclusion that we have the biblical text in a more refined state today than any time in history. We also found from the data of archaeology that the historical content of the Bible is often verified, sometimes to an amazing degree. This is extraordinary when one realizes that those scholars at work in the textual and archaeological disciplines are not doing their work to “prove the Bible.”

Like other reputable scientists, they are searching for truth and analyzing the evidences that come to light. The results have been very encouraging to those who already have an abiding confidence in the Bible as the Word of God. The following examples illustrate the attitude that many have toward the Scriptures who are knowledgeable in the field of biblical textual studies and biblical archaeological investigation.

“There can be no doubt that archaeology has confirmed the substantial historicity of Old Testament tradition” (William F. Albright, Archaeology and the Religion of Israel).

“Scores of archaeological findings have been made which confirm in clear outline or in exact detail historical statements in the Bible. And, by the same token, proper evaluation of biblical descriptions have often led to amazing discoveries. They form tesserae in the vast mosaic of the Bible’s almost incredible correct historical memory” (Nelson Glueck, Rivers in the Desert: A History of the Negev).

“It can be confidently stated that although the primary purpose of Biblical writers was not to compose a history, their writings as an historical source are absolutely first class. Apart from their value as a profession of divine guidance, these several accounts are what we have come to expect of men witnessing to the deeds of the God of Truth whom they worshipped” (John Elder, Prophets, Idols and Diggers: Scientific Proof of Bible History).

Awareness of the principles we have dwelt with in our consideration of God’s Word has caused many who were skeptical of the condition of the biblical documents, as well as their content, to begin a fresh and appreciative approach to Bible study. After all, if it is apparent that the Bible has a solid textual base and shows an accurate historical dimension, isn’t it logical to accept the theological teachings of Scripture on the basis of faith? “So faith comes from hearing, and hearing by the word of Christ” (Romans 10:17).

(Unless noted, Bible translation used is the New American Standard Bible)