Johannine Studies

XII. CONTEMPORARY APOCALYPTIC SCHOLARSHIP AND THE REVELATION

Johannine Studies

XII. CONTEMPORARY APOCALYPTIC SCHOLARSHIP AND THE REVELATION

Subjects reviewed in this chapter:

Introduction – Definitions – The Milieu of the Apocalypse – Characteristics of Apocalyptic Literature – Apocalypticism – Biblical Backgrounds for the New Testament Apocalypse – Approaching the Book of Revelation – New Testament Apocalyptic Antecedents to the Revelation – Why the Apocalypse?

Introduction

It is neither necessary nor possible to give a full survey of apocalyptic literature in this article which has as its primary interest the New Testament Apocalypse. However, for sake of clarity, it is important that several terms be explained which are central to the study. This is essential for two major reasons: First, the literature on the subject often reflects an ambiguity of thought and a tendency to generalize which makes definition of terms elusive.1 Second, critical studies in apocalyptic literature since WWII, and the availability of additional materials such as the Dead Sea Scrolls, have resulted in scholarship which offers new insights and new or adjusted definitions of pivotal terms.

Additionally, the following sections of this paper discuss characteristics of apocalyptic literature. The New Testament Apocalypse is briefly described in light of these characteristics and placed in the broad context of biblical and non-biblical apocalypses, both Jewish and Christian. Specific biblical backgrounds for the New Testament Apocalypse are given. Then, historical and literary features of the Apocalypse are presented. Pertinent New Testament apocalyptic passages precedent to the Apocalypse are examined. The purpose of all this is to prepare the reader to appreciate why apocalyptic language was chosen to express its contents and to expect what is actually found in the Revelation, especially regarding the parousia of Jesus.

Definitions

In this essay, with its special emphasis on the New Testament Apocalypse, the following terms are used according to the definitions given below.

An apocalypse is a genre of revelatory literature with a narrative framework, in which a revelation is mediated by an otherworldly being to a human recipient, disclosing a transcendental reality which is both temporal, insofar as it envisages eschatological salvation, and spatial insofar as it involves another, supernatural world.2

Apocalypticism is a system of thought produced by visionary movements; [which] builds upon a specific eschatological perspective in generating a symbolic universe opposed to that of the dominant society.3

Apocalyptic4 is used in this essay as an adjective5 to describe, e.g., the literary features of a particular apocalypse, or the system of thought and eschatological perspective of a specific type of apocalypticism.6 The inconsistent use of the term “apocalyptic”7 in the relevant literature as both a noun and an adjective has not helped to create the sharpness of perspective needed to deal properly with the complex issues involved.8

Eschatology is also a term which has been cloaked in various garb. For example, with Schweitzer, eschatology became “thoroughgoing.”9 Dodd emphasized “realized” eschatology.10 Bultmann advocated an “existential” eschatology.11 Bowman saw a distinction between “prophetic” eschatology and “apocalyptic” eschatology.12 Robinson developed an “inaugurated” eschatology.13 Ladd opted for a “realistic” eschatology which is confined to the eschatology contained in the Hebrew/Jewish traditions.14 This diversity is mentioned simply to point out that it is essential to delineate terms used in discussing a specialized subject. In this paper the term “eschatology” remains close to its linguistic roots (Gr. eschatos = end, last things). It has to do with telos, the ultimate end, purpose, or consummation of history and the world, (Rev. 22:13). It is vividly portrayed in the New Testament Apocalypse.15

The Milieu of the Apocalypse

When examining the New Testament Apocalypse it is helpful to place it, as much as possible, in its literary, historical, cultural, and theological milieu. From a literary point of view, the genre has a rich heritage. A significant contribution has been made in the last decade shedding considerable light on the nature of apocalypses. It is now known that apocalypses fall into two major groups, those which contain otherworldly journeys and those which do not.16 This kind of classification makes possible an insight enabling better analysis of the various apocalypses; and, importantly for this paper, points out some of the unique features of the New Testament Apocalypse vis-à-vis Jewish and Greco-Roman apocalypses.

The topic of this essay does not call for a discussion of the many individual apocalypses which would be an inherent part of a larger survey of the literature. However, in order to “place the New Testament Apocalypse,” something should be said about its appearance among other apocalypses.

Although the book of Daniel is seen as the only full apocalypse in the Old Testament, it has been repeatedly pointed out that Ezekiel 38-39, Isaiah 24-27, 40-45, 56-66, Zechariah 9-11, Joel 2, and Amos 5:16-20 are apocalyptic sections within these prophetic books. Although it is wise to acknowledge there is dispute among scholars whether certain writings should be included among Jewish and Christian apocalypses, it is probably safe to say that the following non-biblical Jewish apocalypses do in fact “bracket” the New Testament Apocalypse in time and thus give some kind of basis for comparative analysis of the genre during the period they cover. These books are: Apocalypse of Abraham, I Enoch, Psalms of Solomon, Assumption of Moses, Apocalypse of Moses, Sibylline Oracles, Apocalypse of Esdras/4 Ezra 3-14, Book of Elijah, II Enoch, Apocalypse of Baruch, Testament of Abraham, Testament of the Twelve Patriarchs, Ascension of Isaiah, and many of the Dead Sea Scrolls, e.g., the War Scroll.

As mentioned above, along with one full apocalypse in the Old Testament, Daniel, there are several apocalyptic sections. The same may be said of the New Testament. The Revelation is the one full apocalypse, but there are several apocalyptic sections found in other New Testament books. Some of them are Mark 13, Matthew 24-25, Luke 21:5-36, I Thessalonians 4-5, II Thessalonians 2:1-12, and I Corinthians 15.17 Additionally, there are numerous non-biblical Christian apocalypses which stress common apocalyptic themes such as heaven, hell, manifest destiny by God’s bursting into history, etc. Some of these apocalypses are: The Sophia of Jesus Christ, The Apocalypse of Paul, The Apocryphon of John, The Apocalypse of Peter, and The Apocalypse of Mary.18

Characteristics of Apocalyptic Literature19

Compiling a list of characteristics is difficult since no full set fits each document and because general descriptions of apocalyptic literature found in current discussions often fail to draw distinctions between literary features and content. A descriptive approach blending the literary features with the attitudinal positions of the writers provides a framework to note some major literary techniques and beliefs of the apocalyptists.

Pseudonymity is a common trait of an apocalypse. Various conjectures account for this. For example, the “demise of prophecy” made the writer believe that his work would not receive a hearing unless it purported to originate from a great hero of the past. This view is strengthened by the fact that the works are not anonymous; they are almost invariably pseudonymous.20

Many apocalypses exhibit the “predictions” of past events approach to prophecy. Pseudonymity, along with history “predicted” as prophecy (correctly, of course!), would further assure acceptance of the apocalypse.

Use of symbolic language is thoroughly typical of apocalyptic literature.21 This feature was no doubt more than a conventional literary technique, although there is often a detectable conventionalizing of symbols, e.g., the use of gematria.22 Symbolism would allow the writer to convey truths to intended readers who understood the symbols used without that knowledge becoming widespread; or, symbolism could be used to describe reality where literal language would fail.

The pessimism noted in much of this literature has to do with the various writers’ views of the world in light of the general fallen state of mankind. Things would not get better. God was their hope. Most of them saw themselves as living near the end of time, an event which God would bring about. They would then be vindicated and God would be glorified. Their pessimism for this world did not dampen their enthusiasm for the next. God would have the last word. Their salvation would be supra-historical.

Dualism is characteristic of most apocalyptic writings. It becomes very apparent in the contrasting tendencies so often present such as evil vs. good, God vs. Satan, world vs. kingdom of God, this age vs. the age to come, etc. These features show a persistent dualism, but it is not dualism in the absolute sense. Their ultimate view was basically monotheistic.

Ethically, these writings are designed to offer comfort and consolation to the elect, rather than berating or rebuking them. There is, of course, a parenetic element present. Generally speaking, however, apocalyptic literature tends to confirm the stance of the faithful instead of reforming the wicked. This emphasis is likely due to the author's pessimistic view of the world and the belief in the nearness of the End-time.

A chief trait of practically all apocalyptic writing is the deep-seated conviction that all history is predetermined by God.23 This is usually articulated in the literature with episodic or dispensational type of language.24 In a paradoxical sort of way, this view of history was a comfort to the apocalyptists. It gave meaning to the horrors of the world. God would not act until the End-time. It added stamina to their faith. God would, in his own appointed “time,” redeem those predestined to glory. This view also explains the general lack of “evangelistic” emphasis in the literature as implied above.

The concept of revelation is at the heart of an apocalypse. What the apocalyptist wrote about was purportedly what had been revealed to him, i.e., to the great person of the past as indicated by the pseudonym. Thus, the heavenly mysteries, angelic hosts, scenes of hell, judgment, etc., were elements which could not have been known, from the writer’s point of view, except by revelation. Therefore, revelation, for the apocalyptist, did not emphasize God’s working in history so much as the apocalyptic eschatological soteriology of his people.

Apocalypticism

The definition or apocalypticism needs to be recalled at this point because the following enumeration of major beliefs emphasizes, for the most part, the content of the literature in contrast to the literary features of the genre. Admittedly, the fine line between the package and its contents is sometimes difficult to draw. However, for the sake of emphasis, the following beliefs are cited:

1. The radical transformation of this world lies in the immediate future (Dan. 12:11-12; Rev. 22:20; II Bar. 85:10; IV Ezra 4:50).

2. Cosmic catastrophe (war, fire, earthquake, famine, pestilence) precedes the end (Dan. 7:11; II Bar. 70:8).

3. The epochs of history leading up to the end are predetermined (Rev. 20:6ff.; Dan. 9; II Bar. 27; 4 Ezra 7:28; I Enoch 85, 93; Apoc. of Abr. 29).

4. A hierarchy of angels and demons mediate the events in the two worlds (this world and the one to come) and victory is assured to the divine realm (Dan. 10:20ff.; I Enoch 89:59ff.; Rev. 16:14; Apoc. of Abr. 10:17).

5. A righteous remnant will enjoy the fruits of salvation in a heavenly Jerusalem (Rev. 4-5; Dan. 12; II Bar. 50ff,; 4 Ezra 7:32; I Enoch 22:51; Rev. 21; II Bar. 6:8ff.; 4 Ezra 8:52-55; I Enoch 48ff.; Apoc. of Abr. 29:17).

6. The act inaugurating the kingdom of God and marking the end of the present age is his (or the Son of Man’s) ascension to the heavenly throne (Rev. 20:11; Dan. 7:19; II Bar. 73:1; 4 Ezra 7:33; Apoc. of Abr. 18).

7. The actual establishment of the New Kingdom is effected through the royal mediator, such as the Messiah or the Son of Man, or simply an angel (Dan. 7:13ff.; Assump. of Mos. 10:2; Dan. 12:1).

8. The bliss to be enjoyed by the righteous can only be described as glory (Rev. 21:1ff.; II Bar. 30:1; 32:4; Dan. 12:3; I Enoch 50:1; 51:4).25

It is obvious that most of the above apocalyptic beliefs, with slight modifications, are found in the New Testament Apocalypse. What produces such a confluence of religious beliefs? Why are they presented in apocalyptic form? The answers to these and many related questions are vigorously debated in the scholarly literature. This short essay can only address such matters by referring to some major developments in the history of investigation into apocalyptic literature.26

As the 19th century closed, the German scholar Hermann Gunkel was struggling with the question of coherence in the apocalyptic materials. He called attention to the apocalyptist’s use of myth as well as traditional materials to suit his own purposes; thus, the symbolism and the message were of one piece, as the language of poetry is to truth.27

As the 20th century opened, the interest in apocalyptic literature was aroused by the work of Johannes Weiss,28 Albert Schweitzer,29 F.C. Burkitt,30 and R.H. Charles.31 Questions of eschatology were sparked by the two former scholars while emphases on texts and translations marked the efforts of the latter two.

From the 1940’s into the 1960’s perhaps the most widespread and influential works on apocalyptic writings were those of the British scholars H.H. Rowley32 and D.S. Russell.33 One of the major features in their inquiries was their attempts to relate closely Old Testament prophecy and apocalypse, and to show Old Testament prophecy as the primary inspiration for apocalyptic writings.34

Although not the first to advance the theory, Gerhard von Rad took the position that the apocalypse had its roots in Wisdom literature and thought, not prophecy and prophetic traditions.35 Although his position has not received general acceptance, neither has it been dismissed altogether.36

Since the late 1950’s there has been a burgeoning of books and articles on apocalyptic literature. Some major theologians, as well as Bible scholars, have found apocalypticism to be crucial.37 Advancements have been made on many fronts. For example, renewed directions of emphasis in the research have been in the areas of (1) definitions, (2) sources, (3) structure of the apocalypse, (4) time of origin, (5) function of eschatology, (6) Sitz im Leben, and (7) theology.

Biblical Backgrounds for the New Testament Apocalypse Of course, prophecy is a persistent theme running through much of the Old Testament, as well as the New Testament. It is significant that eschatology is a part of both Old Testament and New Testament prophecy. It is also important to note that apocalyptic features appear in both Old Testament and New Testament prophetic contexts. Thus, it is possible to speak of Old Testament prophetic eschatology and apocalyptic eschatology and New Testament prophetic eschatology and apocalyptic eschatology.38

But there is a difference in perspective between prophetic eschatology and apocalyptic eschatology.39 Prophetic eschatology had to do with historical events leading up to the End. Those predicted events were, in the mind of the prophet, the eventual working out of God’s oversight of the world and its history. God was at the helm of reality. All events were in his hands. History was the working out of his will in his own time, and prophetic eschatology emphasized those phenomena pointing toward time's consummation. All of this was according to the telos of God.40

On the other hand, apocalyptic eschatology appears to be mainly expressions of apocalyptists who had “turned loose of history,” so to speak. Despairing of transformation or reformation of this world in this age, they expected God’s sovereignty to be displayed at the glorious End, not in the history of the world.

With this dichotomy in mind, it is easy to empathize with the ecstasy and agony of the Old Testament prophets. In their use of prophetic eschatology, they were sensitive to God’s mighty acts in history which were leading up to the eventual overthrow of all opposing powers and the glorious restoration of Israel and the perpetuation of God’s Davidic kingdom. On the other hand, when they utilized the speech of apocalyptic eschatology they often broke through the historical boundaries. In other-worldly language, they described God’s inbreaking as the End-of-time phenomenon which would usher in the new age in which God’s rule would be fully exercised in his kingdom and his people would be vindicated and exalted.

Historically speaking, eschatology tended to arise in Old Testament prophetic activity when the “the world tumbled in” and the prophets were living and serving during a period of great upheaval, displacement, agony, and distress for them and their people.41 Their prophetic utterances reflect a conviction that, although the present time was terrible and traumatic, God would not forget his people. There would be a rescue operation, a restoration of the kingdom. All this was seen as the consummation of God’s purposes for his people which would eventually be realized in history.

It is not surprising, then, that the historical context of the fall of Judah and the Babylonian captivity in the late 7th century and the early 6th century produced an emphasis on prophetic eschatology.

What happened? The Jews were eventually allowed to return to Judea, beginning about 536 B.C.E. Life under Persian rule was better than it had been under the Babylonians. However, the kingdom was not restored. The Jews were still under subjection to foreign rule. This was followed by Greek domination of the East. After Alexander's death (323 B.C.E.), the conflicts between the Seleucids of Syria-Mesopotamia and the Ptolemies of Egypt reduced Judea to a “political football” kicked repeatedly in the larger struggles of the Eastern Mediterranean world. All of this is too well known to belabor.42

In the post exilic period many of the Jews saw the conditions described above as flying in the face of the prophetic eschatology which had been a comfort and a source of strength for them in those earlier times.43 Even the prophetic voice was silent.44

Why the delay, the agonizing delay? Out of the maelstrom of these post exilic centuries the Jewish apocalypses flourished, both biblical and non-biblical.45 Apocalyptic eschatology came to the fore. Faith in history, as such, was shaken. The previous visions of glory, restoration, and kingdom were frequently pushed into meta-history, where the “new heaven and new earth” would be the stage upon which God would reign in full sovereignty and fellowship with his people.46 How else could the delay, the baffling, traumatizing, agonizing delay, be positively explained? How else could faith harmonize the God of history and eternity?

Approaching the Book of Revelation

This essay is obviously not a commentary on the Revelation. It is not intended to be. It is, rather, an attempt to present the New Testament Revelation as an apocalypse and explain why it was written as an apocalypse.47 By the very nature of the case, scholarship concerned with apocalyptic literature in the past has dealt with Jewish apocalypses and related literature far more than the New Testament Apocalypse and non-biblical Christian apocalypses.48 Therefore, it is not surprising to find that the Apocalypse of the New Testament has several features which are not characteristic of most Jewish apocalypses. First, the book is identified as a prophecy, as well as a revelation, (Rev. 1:3; 22:7, 10, 18-19). Second, it is neither anonymous nor pseudonymous.49 Third, Revelation, in contrast to any other known apocalypses, is set within epistolary perimeters (Rev. 1:4-8; 22:10-21).50 Fourth, the Revelation does not engage in the practice of ex eventu prophecy,51 a common feature of apocalyptic literature in genera1.52 Fifth, and most important, difference between the Revelation and Jewish apocalypses is the emphasis on Jesus, especially his death and glorious exaltation.

It has been said that the “Apocalypse of John is more structurally complex than any other Jewish or Christian apocalypse, and has yet to be satisfactorily analyzed.”53 Since a finalized, undisputed structure of Revelation has yet to be established,54 the following uncomplicated outline is presented here as an aid in grappling with this perplexing feature.55

I.

Prologue 1:1-8

Preface 1:1-3

Prescript and sayings 1:4-8

The seven messages 1:9-3:22

The seven seals 4:1-8:5

The seven trumpets 8:2-11:19

II.

Seven unnumbered visions 12:1-15:4

The seven bowls 15:1-16:20

Babylon appendix 17:1-19:10

Seven unnumbered visions 19:11-21:8

Jerusalem appendix 21:9-22:5

Epilogue 22:6-21

Sayings 22:6-20

Benediction 22:21 56

The Revelation may be best studied in light of its historical context, other apocalyptic literature of its time, its unity as an apocalypse, and the severity marked by Christian martyrdom and false teachers.57 This requires as accurate knowledge as possible of the date the book was written.58 The two dates which have received more serious consideration than any others are 68-69 C.E.59 and 95-96 C.E.60

There is no difficulty in geographically locating the Apocalypse in Asia Minor. It is apparent in the letters addressed to the seven churches that the seer of Patmos is looking to that locale. However, there is considerable dispute of long standing about the authorship of the Apocalypse. The earliest extant witnesses affirmed apostolic Johannine authorship for the Apocalypse. Among them were Justin Martyr [d. 165], Clement of Alexandria [d.c. 220], Hippolytus [d.c. 236], and Origen [d.c. 254]. It was not until the time of Dionysius [d.c. 265] that the apostolic authorship of Revelation was called in question.61 Athanasius [d. 373] won the East back to belief in apostolic authorship after which the church, both East and West, generally held to the Johannine apostolic authorship of the Apocalypse until the time of the Reformation, at which time Luther and others were vocal in anti-apostolic views concerning the authorship of the Revelation.62 The question remains unresolved.

Unfortunately for the question, the author only identifies himself as “John,” (1:1, 4, 9; 22:8). He implies he is a prophet, (22:9), and his book is called a prophecy (1:3; 22:7, 10, 18-19). Fortunately, unresolved questions about authorship, in themselves, do not in any way negate the Apocalypse’s authority, integrity, or importance within the New Testament canon. Although there was a time when many scholars tended to see the Revelation as a composite work, like many other apocalypses, there is now a growing conviction that the Apocalypse stands as a unity from beginning to end, including the epistolary framework, and that it is the composition of a single author.63

New Testament Apocalyptic Antecedents to the Revelation

The reasons why apocalyptic literature flourished among the Jews from about 200 B.C.E. to around 100 C.E.64 have already been discussed above.65 Now, what does one see when the New Testament is opened? The first records to appear after the ascension of Jesus and the beginning of the church were some of the early Pauline epistles addressed to various congregations. In these one finds a strong conviction concerning the imminent return of Christ. For example, in I Thessalonians 4:13-18, Paul states “For this we declare to you by the word of the Lord, that we who are alive, who are left until the coming of the Lord, shall not precede those who have fallen asleep,” (v. 15).66 This letter (5:1-11) and II Thessalonians show the “day of the Lord” was a day of salvation for the righteous and judgment for the wicked (2:1-8), but, of course, it had not come yet (2:2).

In a dramatic apocalyptic eschatological passage addressed to the Corinthian church, Paul ties together in an intimate way (1) the resurrection, (2) Christ’s coming, (3) the “end,” (4) the kingdom, and (5) the ultimate and complete victory of Christ over all opposition, including death (I Cor. 15:24-26).67 Although this is yet future, the language of Paul clearly leads one to conclude that he saw the end approaching. “I mean, brethren, the appointed time has grown very short. . . . For the form of this world is passing away,” (I Cor. 7:29a, 31a). He insists the kingdom of God cannot be inherited by “flesh and blood, . . . but we shall all be changed, in a moment, in the twinkling of an eye, at the last trumpet,” (I Cor. 15:50-52).68

Biblical scholars are aware of the “now” but “not yet” tension present in scripture. There is a present reality to salvation (I Cor. 15:1-2). Justification and glorification for those predestined and foreknown by God are accomplished (Rom. 8:29-30). This “realized eschatology,” mentioned earlier, needs no elaboration here. However, it is clear that the “not yet” is separated from the “now” by the inevitable judgment on that Day (Rom. 14:10b; I Cor. 3:13; II Cor. 5:10).

Between the two poles of “now” but “not yet” the early Christians often lived with anxieties and afflictions, as well as hope and confidence. The longing was to “be away from the body and at home with the Lord,” (II Cor. 5:8b). The Christians faced the future with courage. “He who has prepared us for this very thing is God, who has given us the Spirit as a guarantee,” (II Cor. 4:16-5:10, v. 5 quoted). Paul posited this transcendental possibility of consummate, eschatological salvation in one Person, Jesus Christ, when he said, “Therefore, if any one is in Christ, he is a new creation, the old has passed away, behold, the new has come,” (II Cor. 5:17).69

After Paul’s early letters, one comes chronologically to those Synoptic documents of “good news,” the gospels. The reader is soon reminded of how the Old Testament book of Malachi closed with his apocalyptic announcement, “Behold, I will send you Elijah the prophet before the great and terrible day of the Lord comes,” (4:6a).

The gospel of Mark shows Jesus explaining to the people why Elijah would arrive “before the great and terrible day of the Lord comes.” “Elijah does come first to restore all things. . . ,” (Mk. 9:12a). “. . . But I tell you that Elijah has come . . .” (9:13a). This pronouncement was interpreted by the disciples of Jesus as a reference to John the Baptist, (Matt. 18:10-13). Elijah (John the Baptist), like Jesus, preached repentance in view of the fact that “the kingdom of God is at hand,” (Mk. 1:15; Matt. 3:1; 10:7). Such a proclamation would fan the hopes of the Jews. This was what they had yearned for in the past. But how would this kingdom come about and who would reign over it?

Jesus affirmed he was the answer to such questions. “Truly, I say to you, there are some standing here who will not taste death before they see the kingdom of God come with power,” (Mk. 9:1 and parallels Matt. 16:28; Lk. 9:27). The very keys of the kingdom were promised as an apostolic possession to be used during the lifetime of the apostolic band, (Matt. 16:16-19). Matthew records the following teaching of Jesus, “So every one who acknowledges me before men, I also will acknowledge before my Father who is in heaven; but whoever denies me before men, I also will deny before my Father who is in heaven” (Matt. 10:32-33, with parallels Mk. 8:38; Lk. 12:8-9).

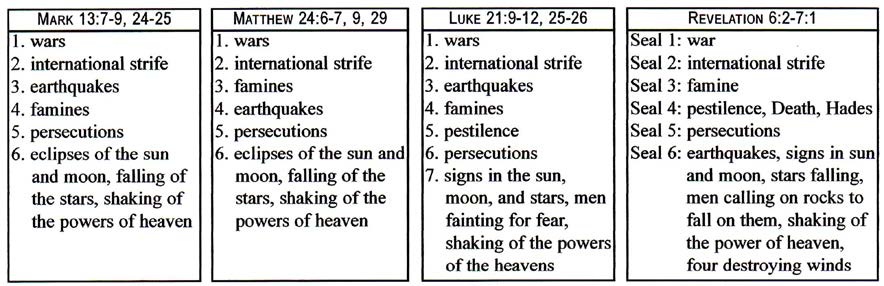

Then, there were those electrifying apocalyptic teachings of Jesus, especially those concerning the destruction of the temple and Jerusalem and the end of the world (Mk. 13 with parallels Matt. 24; Lk. 21).70 No doubt many Jews who heard these teachings believed this predicted holocaust to be the time of their own redemption in the new epoch which would be inaugurated.71 In this context the following words of Jesus would have special meaning to them. “Come, O blessed of my Father, inherit the kingdom prepared for you from the foundation of the world;” . . . (Matt. 25:34).

After his death, burial, and resurrection,72 and the confirming appearances to many of his followers, Jesus continued to teach his apostles, “speaking of the kingdom of God,” (Acts 1:3b). Their eager question was “Lord, will you at this time restore the kingdom to Israel?” (Acts 1:6b). It is difficult for a 21st century reader to catch the sense of immediacy in their question! They actually expected the kingdom at that time, the fulfillment of the hopes and dreams of centuries.

Why the Apocalypse?73

This question calls for two answers. The first answer deals with why the writer chose this genre of literature for his message. The second answer is concerned with why the author said what he did.74

Earlier, it was pointed out that two dates for the writing of the Apocalypse have been defended. If Revelation was written in the late 60’s C.E.,75 the blood of the Neronian martyrs had scarcely dried. If the mid 90’s C.E.76 is the correct date, which is the dominant view, severe trials were also present, but there seemed to be no reign of terror against Christians. However, it is obvious that John was preparing his readers for, and encouraging them to endure, intensified persecutions which would soon come upon them, as well as to stand firm in their present trials.77

A major point arises here as attention is called to amazing parallels between two earlier historical epochs and the history which is unfolding at the end of the first century, and a way in which biblical writers responded to these times.

The era involving the fall and captivity of Judah was initially addressed by some prophets with a heavy emphasis on a prophetic eschatological message. The restoration of Israel would occur. History would see all of the hopes and dreams of a subjugated people fulfilled. However, that did not happen. The kingdom was not restored. The Jews had no more kings after Babylonian captivity.78 They remained under foreign domination during Persian, Greek, and Roman times. It was during these times, especially from about 200 B.C.E., that apocalyptic eschatology became a major theme in Jewish writings. What was perceived as a delay of the fulfillment of the prophetic promises had pushed God’s redemptive work beyond the course of ordinary history. Now, his coming and kingdom would inaugurate the new aeon. There would no longer be “mere” history.79 The transcendental would break into the mundane resulting in a “new heaven and a new earth.” The apocalyptic genre of literature provided the language for this perspective of reality.80 Prophetic eschatology was no longer sufficient to explain the delay and encourage the faithful to endure until the final consummation because prophetic eschatology emphasized God’s working out in history the events up to the End.

This scenario is, in principle, repeated in the New Testament.81 In a sense, Käsemann was right when he made the statement several years ago that “apocalyptic . . . was the mother of all Christian theology.”82 Christianity came into being in a milieu which had fostered high apocalyptic expectations. Thus, many of the teachings of John the Baptist and Jesus were understood in apocalyptic terms.83 And, the spectacular birth of the church, described apocalyptically by the prophet Joel ([Heb. 3:1ff.]; [Eng. 2:28ff.] – Cf. Acts 2:17ff.) as God’s divine breaking into the world with heavenly and earthly consequences, no doubt seemed a logical answer to the apostles’ question put to the resurrected One, “Lord, will you at this time restore the kingdom to Israel?” (Acts 1:6b).

Based upon the apocalypticism of the times, it is not surprising that the ministry of “Elijah” (John the Baptist), some of the apocalyptic teachings of Jesus, and the “fiery” birth of the church following Jesus’ ascension, resulted in a group of Christians who were expecting the imminent return of God’s Messiah.84 The early writings of Paul, discussed previously in this essay, also fostered these eschatological hopes.85 The later Pauline corpus mitigates this stance enough to allow the possibility of his own death before Christ’s return (Phil. 3:10-11, etc.); however, he never teaches anything, including II Thessalonians 2:1-12, that contravenes his early statements concerning the imminent return of Christ.

However, it should be remembered that from forty to sixty years had passed since those anticipatory, exciting times of Jesus' ministry, the flourishing of the first century Christian communities, the early writings of Paul, and the writing of the Apocalypse. What had happened in Christendom between the early and latter decades of the first century? The obvious had occurred. Many Christians had become convinced there had been an undue “delay of the parousia.”86

Later New Testament statements show that this perceived “delay” was recognized and addressed in at least three different ways. First, the “now” of “realized eschatology” tended to mitigate the effects of the “delay” since many of the anticipated benefits of the new aeon were already being enjoyed (Cf. esp. Eph. 1-2). Second, to those who were skeptical of the parousia, II Peter insists that the “delay” is more apparent than real since time means nothing to God. However, the “day of the Lord” is coming with all of its apocalyptic consequences, (cf. II Pet. 3:1-15a).

A third way of dealing with the “delay of the parousia” is seen is the Apocalypse. The epistolary framework is rooted and grounded in history. Seven Asian churches are addressed in specific terms. Their present status is real (probably mid 90’s C.E.). They are assured by their brother that he shares their tribulation, the kingdom, and their endurance (1:9). No doubt he is well known to them, since he is a servant (1:1),87 as well as their brother.

In addition to the seven letters in the epistolary framework, the bulk of the Apocalypse includes the “seven” sections (messages, seals, trumpets, bowls, two sets of unnumbered visions),88 in which the setting is heavenly with earthly perspectives interspersed throughout.89 There are also seven beatitudes found throughout the book.90 The epistolary close may begin at 22:10 and continue to the end.91 If so, here one sees an “epistolary style” summary which includes commands, promises, blessings, affirmation, invitations, warnings, assurances, and a benediction.

The work of the exegete in specifically interpreting these three sections is the task of expositors who have produced a very large number of commentaries on Revelation through the centuries.92 The emphasis here is upon one theme which appears in all three sections, i.e., throughout the Apocalypse.93 It is the assurance to the readers that Christ is coming again and there will be only a brief “delay of the parousia.” Notice: “what must soon take place,” (1:1);94 “the time is near,” (1:3b); “Behold, he is coming,” (1:7); [the One] “who is to come,” (1:8); “hold fast what you have, until I come,” (2:25); “I will come like a thief, and you will not know at what hour I will come upon you,” (3:3b); “I am coming soon," (3:11a); [the angel swore] “that there should be no more delay. . . ,” (10:6b); [God] “has sent his angel to show his servants what must soon take place,” (22:6b); “And behold, I am coming soon,” (22:7); “Behold, I am coming soon,” (22:12); “Surely I am coming soon,” (22:20a).

To say that “the word ‘soon’ (cf. 1:1; 22:6) means that the action will be sudden when it comes, not necessarily that it will occur immediately,”95 is also to say that it may mean soon and not necessarily “suddenly.” This latter meaning seems abundantly clear in this context and is the position taken by many of the major versions,96 commentaries,97 and lexicons.98 Therefore, it seems warranted to affirm that the apocalyptic literary genre, the historical context, and the content of the Apocalypse demonstrate John's earnest desire to encourage his brethren to keep the faith under all circumstances, even “unto death,” (2:l0b). His most effective methodology for doing this is his affirmation that the “delay of the parousia” would not be long.99 His use of the apocalyptic genre emphasizes his conviction that the end of history is at hand, the new aeon is rapidly approaching, and the transcendental reality will soon be the realm of the redeemed when the “offspring of David” comes to close the final chapter on human history.100

It is significant that virtually the final words of the Apocalypse are John’s prayer. If John’s use of “amen” stems from the way Jesus used this term, i.e., putting it first to insure the certain fulfillment of his petition,101 then this short prayer is a virtual guarantee of Jesus’ imminent return. “He who testifies to these things says,102 ‘Surely I am coming soon,’103 ‘Amen. Come, Lord Jesus!’” (22:20).

Footnotes:

1 Klaus Koch, “What Is Apocalyptic? An Attempt at a Preliminary Definition” in: Visionaries and Their Apocalypses [Issues in Religion and Theology, No. 2, ed. Paul D. Hanson] (Philadelphia: Fortress, 1983). See pp. 16-20 where the author discusses what he calls “The Cloudiness of Current Definitions.”

2 John J. Collins, The Apocalyptic Imagination (New York: Crossroad, 1984), p. 4, (emphasis added).

3 Paul D. Hanson, “Apocalypticism” in: Interpreter’s Dictionary of the Bible, Supp. Vol. (Nashville: Abingdon, 1962), p. 28. See Christopher Rowland, The Open Heaven: A Study of Apocalyptic in Judaism and Early Christianity (New York: Crossroad, 1982), for a mitigating view of the role of eschatology in apocalyptic writings.

4 Paul D. Hanson, The Dawn of Apocalyptic (Philadelphia: Fortress, 1975), pp. 11-12. Cited by Barry Ray Sang, The New Testament Hermeneutical Milieu: The Inheritance and the Heir (Madison, N.J.: Drew University, 1983), p. 170. “Apocalyptic is a form of eschatology (and hence a religious perspective) which focuses upon the usually mysterious disclosure to the elect of the cosmic vision of Yahweh’s sovereignty.” Hence, the nominative use of the word ‘apocalyptic,’ contra this essay.

5 T.F. Glasson, “What Is Apocalyptic?” New Testament Studies 27:1 (Oct. 1980). After presenting a very lucid case, this author states, “I would advocate the abandonment of the word Apocalyptic. I know what an apocalypse is, and I see there is a place for the adjective ‘apocalyptic’ to denote matters relating to this type of literature. But, . . . Apocalyptic has no agreed and recognizable meaning,” p. 105.

6 Paul D. Hanson, “Old Testament Apocalyptic Reexamined” [First published in: Interpretation 25 (1971) 454-79]; now in: Visionaries and Their Apocalypses [Issues in Religion and Theology, No. 2, ed. Paul D. Hanson] (Philadelphia: Fortress, 1983). “Apocalypticism is in vogue. . . . there is ample evidence that apocalyptic has come out of a long eclipse into the full light of a wide audience,” p. 37.

7 Koch, ibid., On page 16 the writer states, “The adjective apocalyptic is not directly derived from the general theological term apokalypsis, in the sense of revelation, at all; it comes from a second and narrower use of the word. . . . as the title of literary compositions which resemble the Book of Revelation.” He goes on to say that, “The collective term apocalyptic, which came into use at the beginning of the nineteenth century (Johann M. Sehmidt, Die jüdische Apokalyptic: Die Geschichte ihrer Erforschung von den Anfängen bis zu den Textfunden von Qumran. NeukirchenVluyn: Neukirchener, 1969), can therefore still be retained today,” p. 29.

8 Paul D. Hanson, “Apocalyptic Literature” in: The Hebrew Bible and Its Modern Interpreters [eds. Douglas A. Knight and Gene M. Tucker] (Philadelphia: Fortress; Chico, Ca.: Scholars Press, 1985). Hanson uses “apocalyptic” as both adjective and noun, i.e., as a description of a literary genre and as the genre itself. However, he concedes that “Apocalyptic is a complex and many-faceted phenomenon, and matters are not simplified by the restless development that characterizes its passage through time,” p. 483.

9 E.g., Albert Sehweitzer, The Quest of the Historical Jesus [Trans. W. Montgomery] (New York: Macmillan, 1910).

10 E.g., C.H. Dodd, The Parables of the Kingdom (New York: Scribner’s, 1961). Also Oscar Cullmann, Salvation in History [Trans. Sidney G. Sowers] (New York: Harper & Row, 1967).

11 E.g., R. Bultmann, History and Eschatology (New York: Harper & Row, 1957).

12 E.g., John Wick Bowman, Prophetic Realism and the Gospel (Philadelphia. Westminster, 1955).

13 E. g., John Thomas Robinson, In the End, God. . . . (London: Clarke, 1950).

14 E.g., George Eldon Ladd, “The Place of Apocalyptic in Biblical Religion,” The Evangelical Quarterly XXX (1958) 75.

15 Rowland, ibid., “The fact that the apocalypses offer such important evidence of the dominance of eschatological beliefs within Jewish and early Christian religions is demanding a reappraisal of this element within contemporary Christianity,” p. 447.

16 John J. Collins, “Introduction: Towards the Morphology of a Genre,” Semeia 14 Apocalypse: The Morphology of a Genre [ed. John J. Collins] SBL, (Missoula, Mt.: University of Mt. Press, 1979), pp. 14-15.

17 Paul D. Hanson, “Biblical Apocalypticism: The Theological Dimension” Horizons in Biblical Theology 7 (Dec. 1985), “The New Testament stands . . . as the most important and authoritative guide to the Christian’s interpretation of all apocalyptic writings,” p. 8.

18 Cf. Adela Yarbro Collins, “The Early Christian Apocalypses,” Semeia 14 The Morphology of a Genre [ed. John J. Collins] SBL (Missoula, Mt.: University of Mt. Press, 1979), pp. 61-71 for a survey of twenty-four such texts, including the New Testament Apocalypse.

19 See Ithamar Gruenwald, “Jewish Apocalyptic Literature,” in: Aufstieg und Niedergang der römischen Welt [Herausgegeben Wolfgang Haase] (Berlin-New York: Walter de Gruyter, 1979), Principat. II. 19. 1, pp. 89-118 for helpful insights, esp. on apocalyptic and prophecy, pseudepigraphy, history, and eschatology.

20 Cf. Bruce Metzger, “Literary Forgeries and Canonical Pseudepigrapha,” Journal of Biblical Literature 91 (1972), 3-24 for a discussion of deception, etc., as motives for pseudonyms.

21 Leon Morris, Apocalyptic (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1972), pp. 34-37.

22 E.g., D.S. Russell, Between the Testaments (Philadelphia: Fortress, 1960), pp. 98-101. The extensive use of genaatria is illustrated when Russell says, “The popularity of the number seven is obvious in the Book of Revelation, where it occurs fifty four times,” p. 101.

23 James H. Charlesworth, The Old Testament Pseudepigrapha: Apocalyptic Literature and Testaments, Vol. 1 [ed. James H. Charlesworth] (Garden City, New York: Doubleday, 1983). Here the writer says that within the nexus of pseudepigraphical literature generally, there are at least four significant theological concerns which are often emphasized in apocalyptic fashion: “[1] preoccupations with the meaning of sin, the origins of evil, and the problem of theodicy, [2] stresses upon God’s transcendence, [3] concerns with the coming of the Messiah, [4] and beliefs in resurrection that are often accompanied with descriptions of Paradise,” p. xxix.

24 Martin Hengel, Judaism and Hellenism, 2 Vols. [Trans. John Bowden] (Philadelphia: Fortress, 1974), Vol. 1, p. 181.

25 Klaus Koch, “What Is Apocalyptic? An Attempt at a Preliminary Definition” in: Visionaries and Their Apocalypses [Issues in Religion and Theology, No. 2, ed. Paul D. Hanson] (Philadelphia: Fortress, 1983). First appeared in The Rediscovery of Apocalyptic [Trans. M. Kohl] (London: SCM Press, 1972]. Summarized and condensed from pp. 24-29. See esp. profuse text references, both biblical and non-biblical.

26 Lawrence Boadt, Reading the Old Testament: An Introduction (New York: Paulist Press, 1984). See pp. 511ff. for pointed comments on specific apocalyptic books, a developmental chart of apocalyptic literature, some major elements common to this genre, and “some of the lasting values basic to all apocalyptic thinking that Christians and Jews must never forget.”

27 E.g., Hermann Gunkel, Schöpfung und Chaos in Urzeit and Endzeit (Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 1895).

28 E.g., Johannes Weiss, Jesus' Proclamation of the Kingdom of God [Trans. and eds. Richard H. Hiers and David L. Holland] (Philadelphia: Fortress, 1971).

29 E. g.,Albert Schweitzer, The Quest of the Historical Jesus [Trans. W. Montgomery] (New York: Macmillan, 1910).

30 E.g., F.C. Burkitt, Jewish and Christian Apocalypses (London: Oxford University Press, 1914).

31 E.g., R. H. Charles, Apocrypha and Pseudepigrapha of the Old Testament, 2 Vols. (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1913).

32 E.g., H.H. Rowley, The Relevance of Apocalyptic (London: Lutterword, 1947).

33 D.S. Russell, The Method and Message of Jewish Apocalyptic (Philadelphia: Westminster; London: SCM, 1964).

34 Shaye J.D. Cohen, From the Maccabees to the Mishnah, [Library of Early Christianity, ed. Wayne A. Meeks] (Philadelphia: Westminster, 1987). Cf. pp. 195-201 where the author describes the relationship of prophecy and apocalypse as that of transformation.

35 Gerhard von Rad, Old Testament Theology, Two Vols., [Trans. D.M.G. Stalker] (New York: Harper and Row, 1965), II. p. 306.

36 Contra the definition of apocalypticism given earlier in this essay, if one sees apocalyptic literature with its origins in Wisdom writings, as does von Rad, then another definition is forthcoming. Jonathan Z. Smith, “Wisdom and Apocalyptic,” [First published in Religious Syncretism in Antiquity, ed. B.A. Person, (1975), pp. 131-56]; now in: Visionaries and Their Apocalypses [Issues in Religion and Theology, No. 2, ed. Paul D. Hanson]. Smith states, “Apocalypticism is Wisdom lacking a royal court and patron and therefore it surfaces during the period of Late Antiquity not as a response to religious persecution but as an expression of the trauma of the cessation of native kingship,” p. 115.

37 E.g., cf. below Ernest Käsemann; also Wolfhart Pannenberg, “Redemptive Event and History” in: Basic Questions in Theology, Vol. I, ed. George H. Kehm (Philadelphia: Fortress, 1970), pp. 20ff.

38 See George Eldon Ladd, “The Origin of Apocalyptic in Biblical Religion,” The Evangelical Quarterly XXX (1958) 146, where he makes the observation “that while both Jewish apocalyptic and New Testament apocalyptic developed principles fundamental in the Old Testament prophetic eschatology, Jewish apocalyptic developed in certain non-prophetic directions which sets it apart from its biblical counterpart, which we may describe by the term prophetic-apocalyptic to distinguish it from the non-prophetic apocalyptic of late Judaism.”

39 John J. Collins, The Apocalyptic Imagination: An Introduction to the Jewish Matrix of Christianity (New York: Crossroad, 1984). “In all [apocalypses] there are also a final judgment and a destruction of the wicked. The eschatology of the apocalypses differs from that of the earlier prophetic books by clearly envisaging retribution beyond death,” p. 5.

40 George Eldon Ladd, “Why Not Prophetic-Apocalyptic?” Journal of Biblical Literature 76 (1957), “The underlying theology of apocalyptic eschatology is a view of the world in which the kingdom of God can be realized only by an inbreaking of the divine world into human history,” p. 197.

41 John J. Collins, “The Apocalypse – Revelation and Inspiration,” The Bible Today 6 (Nov. 1981) 363.

42 George W.E. Nickelsburg, Jewish Literature Between the Bible and the Mishnah (Philadelphia: Fortress, 1981). Cf. pp. 9-18 for a brief but helpful historical overview.

43 Richard J. Bauckham, “The Rise of Apocalyptic,” Themelios 3 (Jan. 1978). “Those who now denigrate apocalyptic rarely face the mounting problem of theodicy which the apocalyptists faced in the extended period of contradiction between the promises of God and the continued subjection and suffering of his people,” p. 20.

44 I Macc. 1:41; 4:46. Also, see Gruenwald, ibid., pp. 102-107.

45 Emil Sehürer, The History of the Jewish People in the Age of Jesus Christ (175 B.C. – A.D. 135), 4 Vols. [New English version revised and edited by Matthew Black, Martin Goodman, Fergus Millar, Geza Vermes, Pamela Vermes] (Edinburgh: T. & T. Clark, Ltd., 1986). In Vol. III, Pt. I, Geza Fermes says of the prophetic-apocalyptic pseudepigraphic Jewish literature of this period, “A new type of composition, and the best loved and most influential in this period, is the prophetic-apocalyptic pseudepigrapha,” p. 241.

46 John J. Collins, “Apocalyptic Literature.” Early Judaism and Its Modern Interpreters [eds. Robert A. Kraft and George W.E. Nickelsburg] (Philadelphia: Fortress; Atlanta: Scholars Press, 1986). Although the “Son of Man” phrase was not a title in intertestamental Judaism, “the idea of a heavenly Savior figure was current and provides the natural context for the NT expectation of the Son of Man who will come on the clouds with his angels,” p. 352.

47 James H. Charlesworth, “The Jewish Roots of Christology: The Discovery of the Hypostatic Voice,” Scottish Journal of Theology 39 (May 1986). “We do not come to [the Apocalypse of John] at the end of the canon. There was no New Testament canon in John’s day. We should read the Apocalypse and try to understand its penetrating brilliance in light of the continuum of apocalypses,” p. 40.

48 Joshua Bloch, On the Apocalyptic of Judaism (Philadelphia: The Dropsie College for Hebrew and Cognate Learning, 1952). In speaking of the late Jewish apocalypses, the author states, “Growing excitement and rising despair on the present order furnished the urge to look for the realization of the promise of miraculous deliverance for the righteous and a new era of power and splendor for a regenerate Israel. Naturally in such a day the belief in the advent of a messiah heralding ‘the end of days’ was widespread. The apocalyptic writings in which this belief is proclaimed were very popular, and began to make inroads into Judaism, its votaries drew upon them for support in their claims for the messianic character of Jesus of Nazareth,” p. 45.

49 George Eldon Ladd, “The Revelation and Jewish Apocalyptic,” The Evangelical Quarterly XXIX (1957) 94-95.

50 David E. Anne, The New Testament in Its Literary Environment [Library of Early Christianity, ed. Wayne A. Meeks] (Philadelphia: Westminster, 1987), p. 240-241.

51 Some scholars see in Rev. 17:9-12 an example of ex eventu prophecy. E.g., cf. Bernard McGinn, “Early Apocalypticism: The Ongoing Debate,” in: Apocalypse in English Renaissance Thought and Literature [eds. C.A. Patrides and Joseph Wittreich] (Ithaca, New York: Cornell University Press, 1984), p. 211.

52 John J. Collins, “Pseudonymity, Historical Reviews and the Genre of the Revelation of John,” The Catholic Biblical Quarterly XXXIX:3 (July 1977). “The most basic function of ex eventu prophecies was rendered superfluous by the historical context of Revelation,” p. 333.

53 Aune, ibid.

54 David Hellholm, “The Problem of Apocalyptic Genre and the Apocalypse of John,” Semeia 36 Early Christian Apocalypticism: Genre and Social Setting [ed. Adela Yarbro Collins] SBL (Decatur, Ga.: Scholars Press, 1986). Here a five-fold perspective of Revelation is given based on complex levels of communication, which, according to the author, serve as meta-levels for other levels. This all leads to the most embedded text of the book, 21:5-8, which is probed to eight levels (!), pp. 43-46.

55 Aune, “The Apocalypse of John and the Problem of Genre,” Semeia 36 Early Christian Apocalypticism: Genre and Social Setting [ed. Adela Yarbro Collins] SBL (Decatur, Ga.: Scholars Press, 1986). The reader is reminded to be alert to content and function, as well as form, in studying the Apocalypse, since apocalypses are generically described in the literature in these terms, p. 65.

56 Adela Yarbro Collins, “Persecution and Vengeance in the Book of Revelation,” Apocalypticism in the Mediterranean World and the Ancient Near East [ed. David Hellholm]. Proceedings of the International Colloquium on Apocalypticism, Upsalla, August 12-17, 1979, Tübingen: J.C.B. Mohr (Paul Siebeck), 1983, p. 731.

57 James H. Charlesworth, The New Testament Apocrypha and Pseudepigrapha: A Guide to Publications with Excursuses and Apocalypses (Metuehen, N.J.: Scarecrow Press, Inc., 1987), pp. 19-27.

58 Cf. Adela Yarbro Collins, “Dating the Apocalypse of John,” Biblical Research XXVI (1981), 33-45. Although suggesting a Domitianic date, this article clearly presents the major problems and alternatives. The literature on this point is extensive.

59 Albert A. Bell, “The Date of John’s Apocalypse: The Evidence of Some Roman Historians Reconsidered,” New Testament Studies 25:1 (Oct. 1978) 93-102. Here is an extended argument for the early date with the author’s statement, “The inescapable conclusion is that the Apocalypse was written between June 68 and 15 January 69 . . . . or a few weeks later. . . ,” p. 100.

60 Alan Johnson, “Hebrews-Revelation,” [The Expositor’s Bible Commentary, Vol. 12, eds. Frank E. Gaebelein and J.D. Douglas] (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1981). “Though the slender historical evidence on the whole favors a later date (81-96), in light of the present studies, the question as to when Revelation was written must be left open,” p. 406.

61 Leon Morris, The Revelation of St. John [ed. R.V.G. Tasker; Tyndale House] (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans Publishing Company, 1969). See pp. 25-34 for sources and citations on the subject. His cautious comments point to John the apostle; however, he concedes “the subject is certainly one of great difficulty,” p. 26.

62 “My spirit cannot accommodate itself to this book. There is one sufficient reason for the small esteem in which I hold it – that Christ is neither taught in it nor recognized,” (Martin Luther, 1522). Quoted by G.B. Caird in: The Revelation of St. John the Divine (New York: Harper & Row, 1966), p. 1.

63 See G. Mussies, The Morphology of Koine Greek as Used in the Apocalypse of St. John (Leiden: E.J. Brill, 1971), p. 351 for one author and unity position; cf. Charlesworth, ibid., pp. 24-25 where literary integrity of the Apocalypse is affirmed.

64 Anthony J. Saldarini, “Apocalypses and ‘Apocalyptic’ in Rabbinic Literature and Mysticism,” Semeia 14 Apocalypse: The Morphology of a Genre [ed. John J. Collins] SBL (Missoula, Mt.: University of Mt. Press, 1979), “200 B.C.E. – 100 C.E.,” p. 189. There are variations in the dates within contemporary literature.

65 Michael Brennan Dick, Introduction to the Hebrew Bible: An Inductive Heading of the Old Testament (Englewood Cliffs, N. J.: Prentice Hall, 1988). Dick points to another factor which produced apocalyptic literature, viz., “inner-community strife,” p. 135. The complexities of this sectarianism are discernible in broad outline, but space does not allow their development.

66 J. Massyngberde Ford, Revelation [Anchor Bible; eds. William Foxwell Albright and David Noel Freedman] (Garden City, New York: Doubleday & Company, Inc., 1975). “The oldest apocalyptic text in the N.T. appears to be I Thess. 4: 16-18. It describes the coming, Gr. parousia, of Jesus succeeded by resurrection...,” p. 4.

67 John J. Collins, “Apocalyptic Literature,” Harper’s Bible Dictionary [gen. ed. Paul J. Achtemeier] (San Francisco: Harper & Row. 1985). “Apocalyptic ideas played a crucial role in the formation of early- Christian beliefs in the resurrection and Second Coming of Christ,” (emphasis added), p. 36.

68 Paul J. Aehtemeier, “An Apocalyptic Shift in Early Christian Tradition: Reflections on Some Canonical Evidence,” The Catholic Biblical Quarterly 45:2 (April 1983) 234-237.

69 Walter Schmithals, Die Apokalyptik: Einführung und Deutung (Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 1973) [Trans. John E. Steely] The Apocalyptic Movement: Introduction and Interpretation (Nashville: Abingdon, 1975). Of paramount importance is that “the resurrection of Jesus was originally interpreted as the beginning of the general resurrection of the dead. According to Paul in I Cor. 15:20, Jesus arose as the ‘first fruits of those who have died.’ Thus Jesus’ resurrection signals the onset of the end-events; it introduces the time of judgment and the inbreaking of the new con.” p. 157.

70 F.F. Bruce. “A Reappraisal of Jewish Apocalyptic Literature,” Review and Expositor LXXII:3 (Summer 1975). “Jesus was not himself an apocalyptist. . . . but it was the popular expectations generated by apocalyptic visions that provided the setting for much of his message.” p. 315.

71 Donald Sneen, Visions of Hope (Minneapolis: Augsburg, 1978). Note how Sneen shows the continuity of apocalyptic thought and teaching from Jesus of Mark, through Matthew and Luke, and finally into Revelation, pp. 116-117:

72 E. Frank Tupper, “The Revival of Apocalyptic in Biblical and Theological Studies,” Review and Expositor LXXII:3 (Summer 1975). “The question of Jesus’ eschatological destiny lurks behind all evaluations of the relevance of apocalyptic in Christian theology. Theological inquiry into the definition of man and the reality of God intersect in the question of the historicality of Jesus’ resurrection,” p. 302.

73 James J. Megivern, “Wrestling with Revelation,” Biblical Theology Bulletin 8:4 (Oct 1978). “One does not have to read very much to discover that Revelation has been the most troublesome New Testament book in Christian history,” p. 47.

74 Elisabeth Schussler Fiorenza, “Apocalyptic and Gnosis in the Book of Revelation and Paul,” Journal of Biblical Literature 92 (1973). “The New Testament scholars generally agree that the author of Revelation used the apocalyptic genre to depict the religious and political struggles of the churches of Asia Minor [and that] Revelation was written in a time of tribulation and persecution in order to strengthen the faith, endurance, and hope of the Christians. . . ,” p. 565. Even if the above is granted, the two major questions still remain, the answers to which being the chief purpose of this article: “Why use an apocalyptic genre of literature to ‘depict religious and political struggles’?” and, “What is the central message that strengthens the ‘faith, endurance, and hope of the Christians’?”

75 C. van der Wall, “The Last Book of the Bible and the Jewish Apocalypses,” Neotestamentica 12 (n.d.). “We cannot accept all the arguments of J.A.T. Robinson in his book Redating the New Testament (London, 1976), but we agree with his conclusion that all the books of the New Testament were written before the year 70 A.D.,” p. 116.

76 Frank Stagg, “Interpreting the Book of Revelation,” Review and Expositor LXXII:3 (Summer 1975). “The New Testament Apocalypse probably comes from the time of the Roman Emperor Domitian (A.D. 81-96),” p. 334.

77 Elisabeth Schüssler Fiorenza, “Revelation, Book of,” The Interpreter’s Dictionary of the Bible, Supp. Vol. [eds. Keith Crim, Lloyd Richard Bailer, Sr., Victor Paul Furnish, Emory Stevens Bucke] (Nashville: Abingdon, 1962). “Revelation demands unfaltering resistance to the Roman imperial cult, because to give divine honors to the emperor would mean to ratify his claim of dominion over all people,” p. 745.

78 To be sure, there were dissenting views. E.g., some saw in John Hyrcanus (134-104 B.C.E.) all the endowments of prophet, priest and king to qualify him as a “messianic” ruler, (Josephus, Antiquities, Bk. XIII, Ch. X, par. 7).

79 Much in the Dead Sea Scrolls (ca. 150-B.C.E.-68 C:E.) reflects this perspective from the viewpoint of the Qumran Essene apocalyptists. Cf., e.g., the War Scroll.

80 Charlesworth, ibid., “. . . . we should emphasize that the Apocalypse does not quote any extant apocalypse, nor has it been influenced directly by any of the Jewish apocalypses,” p. 24.

81 Paul Hanson, Old Testament Apocalyptic [Interpreting Biblical Texts, eds. Lloyd R. Bailer, Sr., and Victor P. Furnish] (Nashville: Abingdon, 1987). Hanson speaks of “the apocalyptic message as a pattern woven into the fabric of the canon,” p. 131.

82 Ernst Kasemann, “The Beginnings of Christian Theology,” [Trans. James W. Leitch] Journal for Theology and the Church 6 (1969) 40.

83 See J. Massyngberde Ford, Revelation [Anchor Bible, eds. William Foxwell Albright and David Noel Freedman] (Garden City, New York: Doubleday & Company, Inc., 1975), for the rather startling role assigned to John the Baptist. “Chs. 4-11 contain the revelation given not to John the evangelist after the death, resurrection, and ascension of Jesus, but to John the Baptist, the forerunner of Jesus before his public ministry,” p. 501

84 John E. Stambaugh and David L. Balch, The New Testament in Its Social Environment [Library of Early Christianity, ed. Wayne A. Meeks] (Philadelphia: Westminster, 1986). The writers state that a theme “made most explicit in Revelation but frequently used in Pauline literature and the Gospels, is apocalyptic, the expectation that Jesus will return in ultimate triumph, amid destruction and judgment. In that coming wrath, which was expected urgently and imminently, Jesus would save the believers and deliver them,” p. 58.

85 D.S. Russell, Apocalyptic: Ancient and Modern (Philadelphia: Fortress, 1978). See pp. 41-43 for three other germane elements of N.T. teaching that shaped the apocalypticism of the times which cannot be discussed in detail here, viz., Jesus’ mastery of demons, the concept of the kingdom as mysterion, and the “Son of Man” title associated with Jesus and his parousia in glory.

86 David L. Barr, “The Apocalypse as a Symbolic Transformation of the World: A Literary Analysis,” Interpretation XXXVIII:1 (Jan 1984). “How did this strange book prove to be useful when, on the face of it, it failed rather spectacularly to deliver on its promise that Jesus would come ‘soon’?” Relying heavily on David Aune, The Cultic Setting of Realized Eschatology in Early Christianity (Leiden: E.J. Brill, 1972), he speaks of the “cultic” coming of Jesus in three ways: “in the person of a charismatic prophet, in a visionary christophany, or in a sacramental identification with Christ,” and affirms that all three are present in the Apocalypse “in the cultic personal, in the cultic recitation, and in the cultic celebration of the Eucharist,” p. 48. All this is very intriguing but less than convincing.

87 David E. Anne, “The Social Matrix of the Apocalypse of John,” Biblical Research XXVI (1981). Building on E. Käsemann’s argument that the term “servant” in the Old Testament may be honorific (TDNT 11, 268, 276f.) Commentary on Romans (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1980), p. 5, Aune goes on to say that in the New Testament “the designation ‘servant’ had doubtless come to connote one of superior status (Phil. 1:1; Jas. 1:1; Jude 1:1),” p. 17. Thus, John, writing from “above” to the seven churches, seeks to establish a close communion with his readers by rhetorical terms emphasizing he is “one of them.”

88 Adela Yarbro Collins, “The Revelation of John: An Apocalyptic Response to a Social Crisis,” Currents in Theology and Mission 8:1 (Feb 1981). The “seven” sections (cf. Collins’ outline above) have “the same underlying pattern and thus the same message. The underlying pattern is threefold and involves: (1) persecution of the faithful, (2) punishment of the persecutors, and (3) victory of God and the Lamb and salvation of the faithful,” p. 9.

89 Bruce M. Metzger, An Introduction to the Apocrypha (New York: Oxford University Press, 1957). “The last book of the New Testament contains, in addition to much imagery derived from the Old Testament, a striking parallel to a passage in Tobit. Tobit’s ‘prayer of rejoicing’ contains a remarkable poetic passage which looks forward to the time when ‘Jerusalem will be built with sapphires and emeralds, and her walls with precious stones, and her towers and battlements with pure gold. The streets of Jerusalem will be paved with beryl and stone of Ophir,’ (13:16-17). It may well be that these words were in the mind of John when in the Book of Revelation he describes the New Jerusalem as a city of pure gold, with walls of jasper, sapphire, emerald, beryl, and all kinds of precious stones, (21:18-21),” p. 166.

90 Frank Pack, Revelation, Part I (Austin, Tex.: Sweet Publishing Co., 1965). Pack identifies these beatitudes at 1:3; 14:13; 16:15; 19:9; 20:6; 22:7,14, p. 23.

91 Anne, op. cit.

92 Paul S. Minear, New Testament Apocalyptic [Interpreting Biblical Texts, eds. Lloyd R. Bailey and Victor P. Furnish] (Nashville: Abingdon, 1981). In his chapter, “The Horizons of Apocalyptic Prophecy,” the author relates the theme of Christian vocation to New Testament apocalyptic expectations, pp. 48-63.

93 John G. Gager, “The Attainment of Millennial Bliss Through Myth: The Book of Revelation,” in: Visionaries and Their Apocalypses [Issues in Religion and Theology, No. 2, ed. Paul D. Hanson] (Philadelphia: Fortress, 1983). “The one undeniable fact is that the attention of the community, and thus of its worship, was entirely on the imminent End. ‘The end is near’ (1:3) and ‘Amen, come Lord Jesus’ (22:20) frame the work as a whole as much as they express the mood of its hearers,” p. 153.

94 Martin Rist, “Revelation,” The Interpreter’s Bible, Vol. 12 [ed. George Arthur Buttrick] (New York-Nashville: Abingdon, 1957). “It is essential for the author’s purpose to stress the immediacy of the coming of the end of this age; . . . the author’s own times of course, not ours, being the point of reference,” p.367.

95 John F. Walvoord, “Revelation,” The Bible Knowledge Commentary [eds. John F. Walvoord and Roy B. Zuck] (Wheaton: [Victor Books] Scripture Press Publishers, Inc., 1983), p. 928.

96 E.g., Revised Standard Version; New International Version

97 G.R. Beasley-Murray, “The Revelation,"” The New Bible Commentary [revisors and eds. D. Guthrie, J.A. Motyer, A.M. Stibbs, and D.J. Wiseman] (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1970, p. 1309.

98 W. Bauer, Greek-English Lexicon of the New Testament [4th ed., rev., trans., and augmented by William F. Arndt and F. Wilbur Gingrich] (Chicago: University of Chicago Press; London: Cambridge University Press, 1957), p. 814.

99 Barnabas Lindars, “Re-Enter the Apocalyptic Son of Man,” New Testament Studies 22:1 (Oct 1975). “The delay of the parousia becomes problematical, not simply because of the passage of time, but because of the tension which arises once the death of Christ has been identified as the act in which the evil powers are conquered. To this extent the events of the end time are anticipated, and it is difficult to see why the rest do not follow immediately,” p. 64.

100 Some readers may believe that an absurd, intrinsically self-contradictory position emerges in this essay; i.e., how can one insist, after almost 2,000 years have passed, that en tachei means “soon” in Revelation when it can, and does, mean “quickly” in other contexts (e.g., Acts 12:7). Higher biblical criticism reminds us that beyond a careful consideration of the lexical meaning of a word(s) that, where optional meanings are possible, one must evaluate the word(s) in light of the purpose of the writer, the cultural, historical, and religious contexts in which the document containing the word(s) is written, the primary audience, the literary genre of the work, the immediate textual context in which the word(s) appears, and such like. We suggest that, within limited scope, this essay develops these matters sufficiently, leading to the reasonable conclusion that: (1) the apocalyptic genre was used by John because it was the kind of literature through which he could best accomplish his purpose; (2) his purpose was to encourage, strengthen, and equip his readers to hold firm in the faith in spite of present or anticipated persecutions; (3) his methodology for accomplishing this purpose consisted, for the most part, in presenting a triumphant, reigning Christ returning soon to share his victory with them. How does this affect the way one looks at predictive prophecy? For further study on this question see J.J.M. Roberts, “A Christian Perspective on Prophetic Prediction,” Interpretation XXXIII:3 (July 1979) 240-253. Briefly, the author gives four categories of prophetic predictions. The fourth category touches the question at hand as he speaks of “those predictions whose fulfillment, whether already past or yet to be expected, must be regarded as taking place in a way that is less – or more than – literal,” (Exp. Ezekiel 37-38/Revelation 20:4-22:5). It is within the context of this category that Roberts discusses the characteristic fore-shortening of the time element in most prophetic predictions using Jesus’ statements of his second coming in Mark 13 and Paul’s early ministry as examples. Ultimately, Roberts affirms, “one may try to find the basis for this perplexing problem in the purpose of God himself.”

101 Gerhard Kittle, ed. Theological Dictionary of the New Testament, Vol. I [Trans. and ed. Geoffrey W. Bromiley] (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1964). “The point of the Amen before Jesus’ own sayings is rather to show that as such they are reliable and true, and that they are so as and because Jesus Himself in His Amen acknowledges them to be His own sayings and thus makes them valid,” p. 338.

102 Matthew Black and H.H. Rowley, eds. Peakes' Commentary on the Bible (London: Nelson, 1962). “I am coming soon: this is the motif of the whole book. To our author’s mind, everything depends on this speedy return. He can see no other solution for the Church’s ills,” p. 930b. Cf. also, Robert H. Mounce, The Book of Revelation [New International Commentary on the New Testament, ed. F.F. Bruce] (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1977), where he says, “The verse opens with the testimony of Christ that his coming will be without delay, . . . only in Mt. 28:8 does tachu mean ‘quickly’ in the sense of ‘at a rapid rate.’ . . . Elsewhere it means ‘at once’ or ‘in a short time’ (Mk. 5:25; Lk. 15:22; and the five Rev. passages in which it is used of the coming of Christ: 2:16; 3:11; 22:7, 12, 20),” p. 396.

103 Mounce, ibid., “The words ‘Behold, I come quickly’ are those of the risen Lord. . . . tachu used as an adverb may mean ‘quickly’ in the sense of ‘at a rapid rate,’ although this usage does not fit the context of the five occurrences of erchomai tachu in Rev. (2:16; 3:11; 22:7, 12, 20). It is best to take the utterance at face value and accept the difficulty of a foreshortened perspective on the time of the end rather than to reinterpret it in the sense that Jesus ‘comes’ in the crises of life and especially at the death of every man. Revelation has enough riddles without our adding more,” p. 391. Morris Ashcraft, “Preaching the Apocalyptic Message Today,” Review and Expositor LXXII:3 (Summer 1975). The adequacy of God’s word is stressed. “In the Apoca-lypse, Christ is known as ‘The Word of God’ (19:13). He is ‘Faithful and True’ (19:11). The ‘two-edged sword’ issues from the mouth of Christ, the Lamb (1:16; 2:12; 19:15),” p. 356. This “Living Word” is the one who encourages his followers by testifying “Surely, I am coming soon.”